Entrepreneurial Appetite

Entrepreneurial Appetite is a series of events dedicated to building community, promoting intellectualism, and supporting Black businesses. This podcast will feature edited versions of Entrepreneurial Appetite’s Black book discussions, including live conversations between a virtual audience, authors, and Black entrepreneurs. In this community, we do not limit what it means to be an intellectual or entrepreneur. We recognize that the sisters and brothers who own and work in beauty salons or barbershops are intellectuals just as much as sisters and brothers who teach and research at universities. This podcast is unique because, as part of this community, you have the opportunity to participate in our monthly book discussion, suggest the book to be discussed, or even lead the conversation between the author and our community of intellectuals and entrepreneurs. For more information about participating in our monthly discussions, please follow Entrepreneurial_ Appetite on Instagram and Twitter. Please consider supporting the show as one of our Founding 55 patrons. For five dollars a month, you can access our live monthly conversations. See the link below:https://www.patreon.com/EA_BookClub

Entrepreneurial Appetite

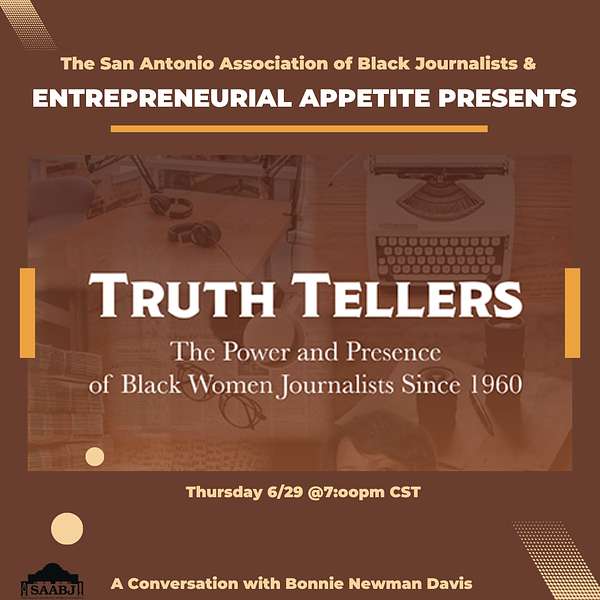

Exploring the Power, Presence, and Impact of Black Women Journalists with Barbara Newman Davis

What happens when a renowned journalist takes on the mantle of a professor? Bonnie Newman Davis, author of "Truth Tellers: The Power and Presence of Black Women Journalists since 1960," shares her compelling journey and gives us an insider's view into the world of journalism. She's joined by the dynamic Melissa Monroe, co-founder of the San Antonio Association of Black Journalists, Cherry Griffin, and Benet Wilson, seasoned veterans of the industry, whose personal narratives illuminate the resilience and dedication intrinsic to the profession.

Imagine a journalism landscape with more black journalists in decision-making roles - how would that shape the narrative? We dive into the significance of the National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) and its initiatives to equip younger members, fostering diversity in newsrooms. Bonnie throws light on the compelling need for ownership in the industry and how it can bring about transformational changes. Whether you're a budding journalist or an industry veteran, you'll learn a lot about the challenges of journalism, the delicate balance between work and family, and handling the fatigue that comes along with the territory.

We also journey with Bonnie into the world of black women journalists, exploring their unique paths, the beats they've chosen, and the value they bring with their diverse voices. Be inspired by the stories of Stacey Adams, Angela Dotson, May Israel, and Dan Hurd, who have all made an indelible mark on journalism. If you've always been curious about the trajectory of journalism through the lens of black women, this conversation is a must-listen!

What's good everyone. I'm Langston Clark, founder and organizer of Entrepreneurial Appetite, a series of events dedicated to building community, promoting intellectualism and supporting black businesses. In this episode of Entrepreneurial Appetite's Black Book Discussions, we partnered with the San Antonio Association of Black Journalists to feature a conversation with Bonnie Newman Davis, author of Truth Tellers the Power and Presence of Black Women Journalists since 1960. Without further ado, I want to give a special shout out to Melissa Monroe. She has been my contact person for this and she is the other half that really made this this evening possible, and so she is the co-founder of the San Antonio Association of Black Journalists and she has brought some of her colleagues here today to be in conversation with Bonnie Newman Davis. And I'm wearing my ANT hat today because Bonnie, like me, is the fellow, Aggie and we, we rep for our school real hard.

Speaker 2:We love our HBCU. So Aggie Pride yeah, melissa, I'm gonna hand it over to you.

Speaker 4:Thank you so much. We are really excited to be on this conversation today. So I just want to give you a little brief background. So the San Antonio Association of Black Journalists and Communication Professionals started back in 1998. When I first came to San Antonio and was starting my journalism career, I saw we didn't have an NABJ chapter, which is National Association of Black Journalists, so we needed an organization to advocate for Black Journalists and we created one. We've been in a community ever since. We have some really strong supporters, like the San Antonio Express News, which is the main newspaper in San Antonio, and Kins TV. They help provide scholarship funding to us every year. So I'm very proud of that and I also have a few of my colleagues here with me to help with the conversation.

Speaker 5:Thank, you, melissa. Hello everyone, my name is Cherry Griffin and I am actually new to the world of journalism so I'm super excited about that. And I got to throw this plug out there because I did a 24-month program in 12. So I'm graduating tomorrow from Frosel University with my master's in new media journalism as the salutatorian of that class, so I'm super excited. And I also teach communications to high school students. I just got elected with University of Texas, austin to teach their college program to our high school students, so I'm super excited about that.

Speaker 1:Congratulations.

Speaker 3:Thank you. Well, I'm Benet Wilson. I was a journalist for 37 years. I am now director of the Pointer Coke Media and Journalism Fellowship Program, which is a year-long program for early career journalists, and I am absolutely delighted to be here. I joined this chapter when I moved here a few years ago and I thank Melissa for her leadership and her help, and I would be remiss if I didn't point out, melissa, that this is our 25th anniversary, so I know it's been strange to say 25 years.

Speaker 4:I don't want to say that you know it's been that long but it really has. And I'm so glad that we can be just a foundation for young black journalists coming through, because we all need mentors, we all need advocates and that was one of the things when I was reading your book, bonnie, that really struck with me because I remember I'm early in the book you said I guess one of the female journalists she saw I think it was someone on TV and her father told her you know, you can be that person one day and I remember my dad telling me that and that's kind of what brought me to the world of journalism in 1998. And I'm still in journalism in many ways and in still part of more black media projects. Super proud of that. But, bonnie, let me go ahead and introduce you and share your bio with the audience.

Speaker 4:Bonnie is a journalist, media consultant and executive director of the BND Institute of Media and Culture, a Richmond Virginia nonprofit that provides programming focused on African American media and culture. In May 2022, davis became managing editor of the Richmond Free Press, which is a 30 year old black owned newspaper in Virginia. She's a graduate of North Carolina A&T State University and the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, davis has experience in print and digital journalism as a reporter, copy editor and editor. Davis also has served in several academic appointments, including a journalism professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and as the Greensboro News and Record Janice Bryant-Hallroyd Endale for professorship at North Carolina A&T State University. Sorry, that's a mouthful there, that's long, alright.

Speaker 4:In 2011, bonnie was named the National Association of Black Journalist Educator of the Year. She has received several awards and recognitions for her work and service, including an Ethel Paine Fellowship to report in Ghana, west Africa, and then, just October of this past year, you were inducted into the North Carolina A&T State University Alumni Hall of Fame in the Department of Journalism and Mass Communications. So, prior to academia, you spent 20 years with the Richmond Times dispatch and Richmond News Leader in Virginia in various reporting and editing positions. You've also worked in newspapers in Kentucky, north Carolina and Michigan, as well as MSNBCs, thegreocom and BlackAmericaWebcom. And then also last year is when you begin your book the Truth Teller the Power of the Power and Presence of Black Women Journalists since 1960. That's when it was published, but I'm sure you've been doing the research on right way before that, and you were married to the late William Haynes Davis and Lawrence Eric Stanley, and you have one daughter, erin Danielle Stanley. So with that, let's go ahead and begin this conversation and, sherry, I'll throw it back to you.

Speaker 5:Alright, first of all, I want to say really excited about being on this panel Reading that book. Being a new journalist to the field, it was very inspirational to me and one of the questions that came up in my mind was why did you choose to focus on Black journalists, women journalists? What was the inspiration behind the book?

Speaker 1:Good evening everyone and I just want to quickly thank you all for having me, the San Antonio chapter and Langston, whom I met on LinkedIn, and I'm so glad to always meet fellow Aggies and also to spend time with fellow women Black journalists. So this is great. I really appreciate it. I've known the NAY for many years. She actually worked with me on the NABJ journal and, as far as NABJ itself, I also co-founded the Richmond chapter Black journalist in 1995. So it's still no, it's no longer in existence, but at any rate we had some great time so back in the day doing that.

Speaker 1:So, sherry, getting to your question, what made me want to write about Black women journalists? Two things. Number one at the time I was teaching at Virginia Commonwealth University here in Richmond and the old saying. You know how the old saying goes if you don't know, you will know, publish or perish right. And so I came into VCU as an associate professor after having been at the Times Dispatch and used the leader for nearly 20 years and there were some other jobs in between and you know, including having a baby and doing some freelance and things like that Landed at VCU and you know that was one of the things that professors needed in the department needed to publish, because every year we have to present these huge annual reports on everything we've done, which I'm Sherry Langston is familiar with. So I instantly thought about Black women journalists because number one, I was one and, due to my long involvement with NABJ, I met so many wonderful people, particularly having served on the National Board, and just you know women from throughout the country who had these fantastic resumes and you know we would get together during convention and board meetings, but outside of that, really didn't know much about these women. So that, and also the fact that at the time, maybe around between 2006-2010, I was heavily involved with the NABJ Journal and when Greg Lee came aboard as president, he asked who is going to be the editor. I think Ernie Suggs preceded me and Greg said you, I was like oh and. So in the span of that time being a writer, becoming an editor, I noticed that many of the profiles featured mostly males, black males, very few women. So at that point I said, hey, we need to tell the story of Black women journalists, and who better than myself to do it? And that's what I did Finally got started on the project in 2015.

Speaker 1:By then I was at A&T as an endowed professor and, as far as you know, selecting the women and deciding who would be in the book and all sorts of things. Right off the bat I knew that it would be a good 10 to 15. Dorothy Gilliam, whom I had met when I was still in graduate school at an NABJ conference in Washington DC. She reviewed my clips back then, gave me encouragement that I had promised and so instantly I knew that you know she would be in the book. Number one and again, women I served with on the board, women I'd worked with in Richmond, women whom I admired from afar. So by the time you know, it was all said and done, there were 24 women. Originally there were going to be about 30, but I was. You know, I was running out of steam by the time I finally sat down to write it in 2020.

Speaker 3:Bonnie, as you look at the journalism landscape now, what work do you think still needs to be done for improvement to the industry?

Speaker 1:Are you talking about print broadcasts or across the spectrum?

Speaker 3:Across the spectrum.

Speaker 1:What work still needs to be done, oh, my goodness. Well, I would say, in terms of diversity. There's always work to be done in that area, in terms of making sure that black women are hired in high ranking positions. You know, it's not enough to just get your foot in the door, but we need to get these women in decision making roles, because so much happens in our communities and, without our voices, so many stories go untold.

Speaker 1:Now, granted, over the past few years, you know, starting with the Kerner report in 1968, which pushed for more minority journalists to come into the nation's newsrooms, there's been, you know, quite an effort, but there have been, you know, dips. And how can I say it? We've seen success in some regards, but not so much in others. For example, when, during the onset of 2000, when many newsrooms started to merge and downsides and all of that, many of us, you know, were the first to go, and I don't know that that has continued, in terms of making sure that more of us are hired for many of those positions that disappeared. Now newsrooms have shrunk, we all are aware of that. So there just is a lot that needs to be done, but at the same time, there has been some progress in terms of women, black women journalists ascending to high ranking positions and I named some of those women you know in my book. I think you all have a couple of black women journalists at print publications there in Texas not so familiar with broadcasts. But yeah, I think that you know ongoing attention needs to be paid to that number one and also training. Sometimes you know we're putting to these positions and without a lot of know how, knowledge, training and all of that good stuff. So that definitely is important.

Speaker 1:In my book Wanda Lloyd talks about how she was with USA Today and Rose to be a high ranking editor there and then she went to the Greenville paper, wherever she was executive editor.

Speaker 1:So there was a concerted effort to make sure that she had everything she needed to be successful when she was with USA Today and I really, you know, enjoyed reading her story and writing about her because it's a blueprint pretty much.

Speaker 1:You know from going to. I think it was some sort of session at Northwestern for two months, if I'm not mistaken, at least three weeks and leaving her baby at home, you know, with her husband and family members. He pushed her to do it, saying, you know you got to do this and during the time she was there there was so much she learned all about financing and unusual operations and just so much, and so that's like that was pretty much unheard of at that time. But you know she, she did it and she was able to come back to her newsroom, take it in a new direction and pay it forward in terms of helping others other young black women journalists, you know be the best that they could be, so hopefully that helps. I'm sure I'll think of some other things too that can be done, but for now that's going to have to suffice.

Speaker 4:Thank you, porta. So, like you were saying, just with the downsizing in the media industry, I saw that here in San Antonio and you know, and I saw the writing on the wall in my career in terms of the layoffs and started looking at that education, pr, field, in which it's a natural progression transition to journalists. But you know, what can NABJ do, since that's kind of like that thread that we've threw all of this from your book into? You know how we are in journalism today. A lot of us share.

Speaker 4:What can NABJ do to just keep the pressure on organizations, companies, that you know they need to constantly diversify and keep it at the forefront, especially in this political climate that we're in with. You know what we see with affirmative actions today with the Supreme Court and what they did. And then you know I think Texas is now the second state behind Florida that just voted down, you know was restricting DEI in colleges and universities. So it's like we're in this very contentious political climate but yet we really need NABJ to still keep staying at forefront and be an advocacy group. And you know what are some things that you think they need to do or could do or recommend that you think they should do.

Speaker 1:Well, one thing I think about in terms of NABJ is the tension that's been given to a lot of our younger members over the past few years, making sure that they are trained and equipped and ready to go out into these newsrooms. No longer can employers say we can't find anybody qualified, which of course, used to be their response to not hiring or making their newsrooms more diverse, and I think NABJ has done a really good job in that regard. I'm sure you know Benet, who's worked with a lot of those young people, would agree in terms of offering them training during the convention, with the print magazine I'm not so sure that it's still print, but I know it's online and with the journalism, with the broadcast training and perhaps even radio and podcast and all of those things. So and I say that because at one point it seems like there was not really much going on for my generation or maybe you know members 10, 10 years younger or whatever it seems like the focus was mainly on young people. So I applaud NABJ for that, because you can't go into these newsrooms and make no noise about there not being enough diversity when you don't have a talent pool. So that, in and of itself is there because I've judged a lot of contest for students who are seeking scholarships and things of that nature through NABJ. I encourage young people all the time, advise and mentor. I've been a mentor and advisor to NABJ group, you know, at the various universities. So that's definitely there and so I would say for those students, even with coming going to the convention a month from now in Birmingham, I know students at some of these majority institutions who may have an NABJ chapter but don't have any resources to get to the convention, nor are they getting guidance, oftentimes because they don't have black professors in those spaces.

Speaker 1:So, paying more attention to because sometimes I felt, like you know, working at VCU, I felt, often felt like I was just out there by myself. Fortunately, because of the type of person I am, I'm always, you know, looking for resources and reaching out to others and asking for help and things of that nature, but at the same time that's not necessarily encouraged as much as maybe, for example, sbaj or some of the other student organizations. So I think, a real focus again on making sure that these students, these young people, have access to NABJ, to its programs, that they are properly trained, getting you know members into these classrooms and making sure that they know how to write and edit and copy, edit and investigate stories and all of those good things. Because, you know, I'm in a position now where I can hire young journalists. So that's what I'm looking for, particularly being a weekly newspaper with not a lot of resources, so we can't afford, you know, to spend a lot of time training young people.

Speaker 1:And then there's also something happen, say, for example, if a well-known journalist is fired, or NABJ, or something happens, and NABJ, you know, usually puts up press release or whatever, or demands action, or demands to sit down with some of these corporate heads and things of that nature. Well, that's happened over and over for the past few years and it would be good to know what is the outcome of these meetings. I don't know that. We always know. And then you know what types of negotiations are going on. We hear about an NABJ met with some corporations. This is what was stated.

Speaker 1:I think it was ABC, where there was a big brah-ha a couple years ago, and but then that's it, and after a while, things you know sort of go back to being the same. So again, it just goes back to making sure that more of us are in decision-making positions. I think ABC does have a black woman in charge of news and CVS as well, maybe a couple of black women. I know that Gayle Keen calls out the name of a black woman quite candid on the morning show NBC. I don't know what's going on there.

Speaker 1:So, and ownership, of course we have to talk about ownership. You know, owning our own. So I have to give a shout out to Kathy Hughes, who has done the do done, due diligence in making sure. Well, she owns Radio 1 and you know all sorts of other properties and ventures, and she's very active here in Richmond, as a matter of fact, because right now she's trying to get this casino in town and that means jobs and just all sorts of opportunities for our community. So we'll see where that takes us. But Byron Allen and who is it? Tyler Perry, who's the BET that was rumored that he may be interested in purchasing. So all that filters down to jobs. Maybe, you know, when you talk about NABJ, there maybe needs to be more focus on how we can grab those opportunities.

Speaker 5:Yeah, so, bonnie, I want to talk about something you just said about the talent pool, and I can speak from starting coming into the journalism the, my alma mater, there wasn't anyone like me in the program.

Speaker 1:Right.

Speaker 5:So the only thing that was pushed to me was public relations, and that's just not what I was interested in. It wasn't until I was exposed to just really going online and looking and finding out myself where are we and what do we have? Something that you said was really key there about the training and getting the talent pool to where we need it. So what my question is, with the constant changes in journalism, and especially with black journalism, what do you think black women in journalism need to do to either reinvent themselves or invent themselves in this journalistic role?

Speaker 1:Well, I don't know necessarily that I should be saying that this is what they need to do, but I know what I did and I have always freelanced. In addition to having full time job or part time job or no job, the ability to write has taken me many, many, many places A sense of curiosity, a sense of just wanting to know and to be able to put something on paper that people will read. So the opportunity is definitely there now, with technology and the ability to create a blog or your Instagram or your Facebook or the LinkedIn. I mean, it's just endless. And those mediums weren't around, of course, when I started out, and perhaps a couple of you, but they're there now and I've taken full advantage of them, which is how I've been able to get noticed, even if I'm writing, for there were times when I was writing for publications that only paid like $75 an hour, which is nothing, but I would, you know, take the job and then I would post my article online and after a while, people you know a lot of people actually take notice of that and before long, I was getting calls to do other articles for larger publications for more money.

Speaker 1:And, for example, when I moved back to Richmond after teaching at North Carolina A&T for I think it was about four years as an end out professor. I didn't have a job. I did work for the free press, where I'm working now. For about eight weeks I had an internship I like to call it that and but after that I think I was just hired so and I was supposed to teach at North of State, supposed to teach an ethics class, but I was like you know what? I just need to sit down and rest. And in doing that we're still doing a lot of work with NABJ, some consulting and whatnot. Every time I look and bin there, I remember NABJ in the house, and so that's when I started my institute by non-profit.

Speaker 1:And the idea for that really came when I was working my internship with the free press. I was writing and copy, editing things like that, because one of the features that we have in the papers, the standing feature called personality and it usually highlights someone in the community who is either president or has a leadership position with a nonprofit. And at that time and still we need to get back to it but I noticed that there were some young black women who were heading up these non-profits. That had to do with all sorts of things, but some of them, you know, were born out of violence or abuse or things of that nature and they were doing well. So I was like that's an idea.

Speaker 1:So I'd always worked with students and what came to mind was the Dow Jones program, the minority internship program, which I helped run when I was at BCU and also was a part of it when I was at the Richmond Times Dispatch. But the main thing is and we just celebrated our 44th year having a reunion for the first time in 44 years the Dow Jones Minority Interns Class of 1979. So I was in that very first class. There were 11 of us and nine of us are still living. So Shirley Carswell brought us all to Philadelphia for a reunion and we talked to this year's.

Speaker 2:Hey everyone, Thank you again for your support of entrepreneurial appetite. Beginning this season, we are inviting our listeners to support the show through our Patreon website. The Founding 55 patrons will get live access to our monthly discussions for only $5 a month. Your support will help us hire an intern or freelancer to help with the production of the show. Of course, you can also support us by giving us five stars, leaving a positive comment or sharing the show with a few friends. Thank you for your continued support.

Speaker 1:Oh, group of students. So I was like, you know, I need to do something like that and I came up with the idea of a nonprofit, which one of the aspects of it is the summer media camp introducing young students, young people, middle school and high schoolers to careers in journalism. So, yeah, so that not very profitable and very fulfilling. And I was offering other programs as well, similar to this, but we were going in person before the pandemic occurred and actually so I started this to the 2016. So it was really starting to take off. You know, right, as the pandemic took off, I mean I was getting grants and support and people were starting to recognize who I was, because even I had worked in Richmond all those years, back for 20 years, and everybody knew me. You know, people acted like they didn't know who the hell I was when I came back. So it has definitely been full circle. To answer your question Keep those skills going.

Speaker 1:When I left that Dow Jones internship program, I felt like I could take on anything. I had that under my belt. I had two internships, maybe three and three, and two strong institutions A&T, where it all started, michigan so, you know, had nothing to lose. One of my first freelance articles was with Black Enterprise and that was like in 1981. So I had, you know, had that going for me, and then you know being thirsty and being needy. So when you talk about need, you know when you need money to pay the bills, to feed the baby, to feed yourself, to help your family. You know to look good, smell good, drink good, look good, all those things, dress good. You got to find the work. You just you better be ready, you know, to put in the work. It's fun, it's fun. I love journalism. I hate to admit it sometimes, but I do and wouldn't trade it for the world.

Speaker 5:Well, you answered the second part that I was going to ask, and that was you know if you start teaching high school schools. What I do now, part of my job is I we're at in San Antonio Preparatory School, where a majority of it is minority students brown and black kids and so we brought this year I brought the media program, so we started our essay prep TV and I'm teaching them what journalism is from what I learned from NABJ and then from just being around the journalists that I've attached here, following everyone and learning what I can. So that's that's something that it's good to know that I'm moving in the right direction at starting young, you're never too late or never to start something.

Speaker 1:That is not an easy job, but it's so worth it, and you learn so much from young people too. That's what I. That's my joy.

Speaker 3:Oh well, speaking of young people, bonnie, you know how I feel about the young NABJ students, but what I have seen in the past few years, especially my female mentees, they're tired, they're exhausted, they are drained from being in journalism and they're leaving, and it breaks my heart. But I also understand what they're doing. So what can I say to them? I don't want to discount what they're going through, I don't want to talk them out of journalism, but I want to emphasize that we need them. So what advice would you have? So what do?

Speaker 1:you say in their leaving what, after two or three years, five years, 10 years?

Speaker 3:Anywhere from two years to 10 years. So far, I don't know.

Speaker 1:I think maybe it's a different generation. When you say they're tired, that could be due to any number of things. I mean, you know, when you look at all the things that young people, this generation, they've had to go through, and then to get the degree, get the job and then be confronted with the type of hours that they have to work, different types of people they have to work with, personalities, all of that it's tough. It's tough. And you know we're hearing now about all the mental health issues and challenges that so many young people are going through. And so you know I'm reluctant to say you know, try to encourage them to stay. I think those who really have a passion for it my Ashley Wilson, you tried to steal her from me but she's my who's at the Washington Post. She doesn't stay at a job long but I'm sure she'll be at the Post for a while now that she's back and closer to home and all that good stuff.

Speaker 1:But I don't know. That's a hard one, because I was ready to leave after. I think I left in from 81 until 80. Aaron was born in 88. So I was at, you know, my employer for seven years and then I left. But I still stuck with journalism because I left to work for magazine and then the magazine fold it and so I went back because one I knew I could and two I missed it. You know I missed it. So when I went back I stayed for another 10 years or so. Again, it's a skill that you can take with you.

Speaker 1:So I think most people I've heard so many people say you know I took a journalism class or I started out of journalism. One of my dear friends who was in the Dow Jones program with me, valerie Montague, northwestern graduate who had great jobs in various newspapers, but she left after about five years and that broke my heart. I told her recently I couldn't believe it because she was so good. But she's saying that you know the crummy hours and you know she'd get off at midnight and you know would have to walk or ride or something by herself and so it just, you know, didn't work for her.

Speaker 1:But it's, I don't know it's a hard it really is. I can't say what I would say, except for those, because people are, you know, they have to make up their mind and go their own way and you know a lot of them do find their way back and whatever experience that they get while they're out there is going to be, it's going to be helpful when they do, or if they do return to the newsrooms. Yeah, what would you say to them? Or what have you been telling them?

Speaker 3:Well, I've been telling them that in the end they have to take care of themselves. I tell them I really wish you wouldn't leave journalism. We need you, but if it is causing you this much stress to your mental health, then if you have to go, then you have to go.

Speaker 1:That's right, yep, and that's a tough business it is. I can remember when I told my family that I was going to be a journalist and my sister she was my older sister she said oh, why do you want to do that? I'm a journalist and drunk Like what? Yeah, she did Some of it is true, but again, it's a hard sell. Some people do not have a clue or understand what it is you're doing, why you're doing it To this day. I don't think people really know. Well, I know they don't know because, being a black newspaper, we get so many requests for things that we can't do simply because there are no resources. We're free newspaper number one and just because we're free, that doesn't mean that we're going to write about your 50th wedding anniversary or something along those lines.

Speaker 2:We might consider it and you can always buy an ad, but you know, I wanted to jump in real quick and ask a follow-up question to the burnout situation of the young women in journalism and as a college professor, I see just burnout among young people as something I didn't even really experience in undergrad. It may be a bit more pervasive now than it was before, and I think about all the narratives since 2020 about us being fixed in a state of oppression and racism and things. That's what's gonna be draining and then having to report on that constantly, right. And then I think about the title of your book, Proof Tellers the Power and Presence of Black Women Journalists. And I'm wondering how do you see opportunities for black women journalists to report on things that fill their spirit?

Speaker 2:Think about 1960, I don't know. James Brown came up, say a lot on black and I'm proud, Like there's a lot of stuff going on back then, right, but I don't as much of all the things that was going on with integration and I think my Ida B Wells and like the Toad maybe took on her to do all of these lynching reports and things like that. But how was there a space created in the culture where we are doing celebratory news stories and not just these things about what it sucks about being black.

Speaker 1:Well, sometimes we have to report on the tough stories. That may not be so appealing but it helps. It serves as an entree, so to speak, in terms of how we can get to the celebration. Or there are certain stories, for example Kat Shepard-Saffert, who works for the Associated Press. She's based in Detroit and she has written a five-part series about black health disparities, and so she talks about black female maternity mortality. She talks about dementia among our elders, teen suicide or teen deaths, just the whole cycle of what we as black people go through. It's a story that's been told before, but it's a story that needs to be told and she's done a great job of telling it, and continually. Because in telling both types of stories and how, the mistreatment, the history of black women, their bodies being used and tortured and butchered, pretty much for science, it makes us more aware of our history and what has happened and why it's so important to tell those stories and what can be done and making sure that we see healthcare practitioners that we trust, who have our best interests at heart. Because I can remember, you know, my mother telling me I'd had a surgery for a couple of surgeries, minor but still back in the day, you know she was saying that. I can remember saying stop letting them cut on you. And this is. You know I was growing and out of the house and working and all that, so that's always stayed with me, but she didn't tell me why. She said and I guess I didn't ask, I just you know, if your mother says it can you do what she says. But it's so much more there and so now thank God we have these reporters who are sitting at the table and making sure, because I know Sandra Ross, who's in the book, and she worked for the Associated Press and she had a really, really hard time convincing them of certain stories that need to be told. So here we are, at least years later after Sandra. Sandra started and this woman has written it. Hopefully it will be published in a book form because it's that good.

Speaker 1:I ran, I've been running the series in my paper and it takes up like a full page to run one series and so I tried to break it up. So people want tired of reading all the type to make it more appealing. But hopefully people are paying attention. So that is one of the ways and so many black women are publishing these days and black women are on the increase. Aside from newspapers and broadcasts and journalism, black women own businesses have increased since the pandemic, I think, either through our own funds and finances or from some of the programs that came about as a result of the pandemic or whatnot. But so we're using our resources and self publishing, like I did with my book, and also just telling our stories, which is so important. I mean, people are clamoring like what is it? Merida Golden, she's still writing. You know, she's still out there.

Speaker 1:The women that I met with in Charlotte this past weekend who are in the book May Israel, fanny Flono, patrice Gaines, who's been publishing like forever, used to work with a Washington Post. May used to work with a Washington Post, fanny held it down in Charlotte and they're still. You know these women are in their 70s, late 60s, 70s and they are still holding it down publishing. May was on deadline for some projects she's working on. So I think, as long as we continue to educate ourselves and stay on top of what's going on and stay active and stay healthy the sky is the limit. It is and surround yourself with young people who can help you figure things out that you may not know, if you can get their attention.

Speaker 4:Sherry has a follow up question, right.

Speaker 5:Yes, I do, and Langston thanks for asking the question because it was on the tip that I wanted to say. So a lot of what I've been and what he said about talking about things that matter on the freelance side. What advice would you give to someone who's like, well, I don't wanna go in the newsroom and fight those challenges, but I do wanna report on stories like Black Lives Matter and the things that are happening within our community? What would be your advice to that type of journalist or that person that has that fire to do that?

Speaker 1:Just start writing and, you know, don't be afraid to ask questions because there are a lot of people out there who want to be heard. Remember telling one of the young men he has been freelancing for us since he left college and we've decided to hire him full time. His name is George Copeland and he definitely has, you know, firing the belly and he's been loyal, consistent, you know, does pretty much anything I ask him to do, does it in record time. So, yeah, why not hire him and give him a chance? And so he'll be covering schools. But he can, you know, pretty much handle just about anything. So I would say, you know, be present, make yourself known, do enterprise reporting. You know work, your sources and all those good things. And I remember George asked, you know, saying, mentioning with schools, that he doesn't really know that many people who hasn't developed sources, and I said, don't worry, you will, because people love to talk.

Speaker 1:You know, I've had to relearn that but you know they may not talk on the record but they're out there willing to give you that information, because so many news organizations are no longer in existence. So we're fortunate in that regard because people tell us all the time because that we're recording things that other news organizations locally do not. So yeah, so just you know, be willing to do the work and everything else will just sort of fall in place.

Speaker 5:Thank you for answering.

Speaker 4:We have a question from one of our attendees, so this is a multifaceted question and it's about dynamics and being able to pivot. So I'll ask both the questions and I may have to do the second one again. See, can you speak to in your book what are the patterns of black women journalists? Versatility Was journalism something they went full foresad or were there other things that they did to help strengthen and direct them to that field? And then the second part is how did you find your beat? What beats do you think that are? Is it a necessity for more diverse voices In your book? Did you find early female black journalists in a few specific beats or was there a range?

Speaker 1:So first one is just basically versatility, yeah, okay as far as what brought them into journalism. Did they do something else and just sort of fall into it? I think was the first question. I can say for the most part, many of the women in the book had experience either early on as young as elementary school with writing. Stacey Adams, for example, who lives here in Richmond, you know, wrote a story and got invited to take a tool with a policeman and that made her realize the power word at an early age, and so it just continued from there. Now, stacey, she's not only been a journalist, and award-winning journalist, but also written about 11 books Because so it took her in that direction. She's no longer in a newsroom, she works as a marketer for the fed, as a matter of fact, but she still writes and she conducts workshops and just all sorts of things that the field has taken her to. Angela Dotson started writing early, ended up at the New York Times. May Israel started writing in high school. Dan Hurd, I don't know. She planned to be an English teacher but ended up as a leading editor of the Washington Post.

Speaker 1:Myself I didn't know what I was gonna do until college and having met Sandra Hughes, the local she was on television, first black woman to have her own talk show in Greensboro, and so that sort of lit the fire, I would say, when I was in high school, because she came to speak to my high school class. But it wasn't until I took my first journalism course and my professor had the article published in school newspaper and then the local black paper picked it up. So seeing your name and print, nothing beats that and that sort of did it for me. But I didn't have a clue what I was gonna do. To be honest, I did know by the time I left A&T because I had had an internship and I'd done so much.

Speaker 1:After I sort of found my footing. But I also knew that. I knew I was gonna be a journalist. But I also knew that I wanted to teach at some point, because college, because I had really really good professors in undergrad and grad of course, but, yeah, black women professors who knew you know. So I would say most of the women had a pretty clear idea from the start. Now there were some detours along the way for many of them. Denise Bridges she's the first chapter in the book. She hit a wall a couple of times to the extent that she was about to take a job either selling cars or as a forklift operator and then made her called. You know, just in time. See what a waste of talent that would have been. So a very diverse group of women, but all who settled on journalism as a career.

Speaker 4:The second part was are there certain beats that you think are necessary to have more diverse voices? Well, every beat needs a diverse voice, but are there specific beats that I guess they all kind of gravitated to or fell into, because they were black female journalists or just from what you found in your research, that they're just across the rank?

Speaker 1:Uh-huh, uh-huh, trying to think I mean For the most part, well, they're okay, beats because there was a big push at one point to get more blacks into copy editing which could be more lucrative or was a more direct path to upper management or leadership. So black women copy editors, which there never was in the newsrooms. I worked for an overwhelming amount of black women one or two at the most, amount was it from what I recall. Business, of course. I think business, I love business, writing. I think it's just so exciting learning you know how money is made, learning how people work and why they work, and all those things.

Speaker 1:I think my interest in business will spark. Growing up, with my parents sitting around at the dinner table talking about you know their day's work and potential of possibility of unions, you know coming to town or pay and their salaries and things like that, so that always kind of piqued my interest and so I became a business writer, a copy editor and columnist. Everybody loves entertainment, arts and entertainment, so that was a natural for me. I was arts and entertainment editor before I left the newspaper and also covered fashion, which that was the first, and probably I can remember going to the shows in New York and other places and there was a smattering of a not a lot, but you know a handful but mostly white women, white males who covered fashion. So for some reason my editor, you know, because I actually left the

Speaker 1:paper after seven years, stayed gone for maybe two and a half years, went back and that was a job that was open. I was no longer in news and so that worked out. That was fun, but after a while I got tired of it was like you know, trying to see it, seeing skinny women, black and white, because I was not skinny, I had not been skinny since college. So, yeah, but it was fun. It was fun. I got to, you know, meet and see a lot of you know the high dollar people, celebrities. Then, you know, seeing Jackie Kennedy before she passed at a fashion show, carolina Herrera, that was special.

Speaker 1:Other beats definitely environmental I think we're needed there healthcare, which I covered a little bit when I was in business, but more so from the corporation side, and politics. This is like so interesting today to see, with the Supreme Court decision announcement, black people I had not seen since the last election on air. I was like here we go again. You know, where have these people been? So what is up with that? Can anybody tell me please? Yeah, yeah, but we're always needed in those arenas and it was good to see them because they're so full of knowledge. I mean Eddie Goward, he's a professor, but he's, you know, really good, really knowledgeable, and so it would just be nice to see them on a more regular basis, for sure.

Speaker 2:So, bonnie, your question segues really well to the question that I want to ask. Glad that you brought up affirmative action and I'm going to say something that might be slightly controversial. I believe that we had already reached a point of diminishing returns in DEI work. Personally, I think it was as far as it was going to get. I think it had reached the point where I mean this is my quote, I'm pointing this term that that DEI in a lot of ways, is reverse reparations for white institutions because they already have the money. They have the money to have the resources to do it.

Speaker 2:What happens is these special programs get made, grants, get allocated all these resources and they still do a bad job of it. They suck at it, so they get engaged for doing a bad job. And so I'm familiar with the Maynard Institute and I read the story about how the Maynard Institute is the woman who was going to go work in construction. She's a legend. Now, right, this is a really good work.

Speaker 2:So it's hard for me to critique something like that that has done good work and maybe save some people, but me personally, it's at Cal Berkeley right now. Cal sucks when it comes to black and brown people, so why should they get that program right? Right, shouldn't A&T get that program? Shouldn't family get that program, shouldn't they? And to me, I think there needs to be a shift more towards building black institutions, rather than taking this diversity initiative and putting it in a PWY that has already been created that it doesn't do a good job of it. So I would like to get your thoughts on the removal of D&I programs and a placement and investment in them in institutions that have already demonstrated their ability to do the good work?

Speaker 1:Yeah, for the most part. We've seen the reports recently about the failure, like you say, of these D&I programs and elimination of many of them. Again, if you're going to do them, do them correctly. Have people in place who know what they're doing and are passionate about it the leadership, because they can be effective. But you've just got to be hardcore about it. I have a friend who does it with her university, among many other hats that she wears, and she is just hardcore in terms of making sure that her employees know and they're in communication. So it's from top down and making sure that everybody else in her department that it filters down, even the board members. They have to be trained and knowledgeable about D&I and it's important. Again, if you're going to have it, it needs to be done correctly. If you're not and it's a mess, like you say just leave it alone. Give the money to other institutions where it can be helpful.

Speaker 1:I read an article yesterday where Hampton University was given and I ran it in my paper too was given $750,000, which isn't a lot of money because it has to be divvied up among all these other universities, right. But what it did mention was that Ken Schumann, formerly of American Express. He's involved with this project. There's some sort of financing fun, equity fun, I don't know, but it's designed for these universities to build endowments through some sort of equity partnership fund or whatever. But then I left that alone and went to his page just wondering oh okay, yeah, he was with an enterprise.

Speaker 1:What is he doing now? And so he says it very clearly and succinctly on his website that his goal is to make sure that Black people are given or have the opportunity to have these resources available to live the lives they deserve. Basically, I'm paraphrasing, but I say, wow, this is powerful. And so if people like him and Mr Smith from Denver I can't think of his words, robert Smith and some of these other, you know, I've always thought why can't we do it for ourselves? Why do we have to look to others to do it for us? And if not now, when? When can we do it for ourselves? Yeah, that's my take on it.

Speaker 2:All right, so I think that was a great way to end Bonnie Newman Davis Aggie Pride. I want to say Aggie.

Speaker 2:Pride. That's our thing. And the three other women who joined us here today Cherry Griffin, renee J Wilson and Melissa Monroe, the co-founder the San Antonio Association of Black Drawers. You all for curating this conversation. Thank you for joining this edition of Entrepreneurial Appetite. If you liked the episode, you can support the show by becoming one of our founding 55 patrons, which gives you access to our live discussions and bonus materials, or you can subscribe to the show. Give us five stars and leave a comment.