Entrepreneurial Appetite

Entrepreneurial Appetite is a series of events dedicated to building community, promoting intellectualism, and supporting Black businesses. This podcast will feature edited versions of Entrepreneurial Appetite’s Black book discussions, including live conversations between a virtual audience, authors, and Black entrepreneurs. In this community, we do not limit what it means to be an intellectual or entrepreneur. We recognize that the sisters and brothers who own and work in beauty salons or barbershops are intellectuals just as much as sisters and brothers who teach and research at universities. This podcast is unique because, as part of this community, you have the opportunity to participate in our monthly book discussion, suggest the book to be discussed, or even lead the conversation between the author and our community of intellectuals and entrepreneurs. For more information about participating in our monthly discussions, please follow Entrepreneurial_ Appetite on Instagram and Twitter. Please consider supporting the show as one of our Founding 55 patrons. For five dollars a month, you can access our live monthly conversations. See the link below:https://www.patreon.com/EA_BookClub

Entrepreneurial Appetite

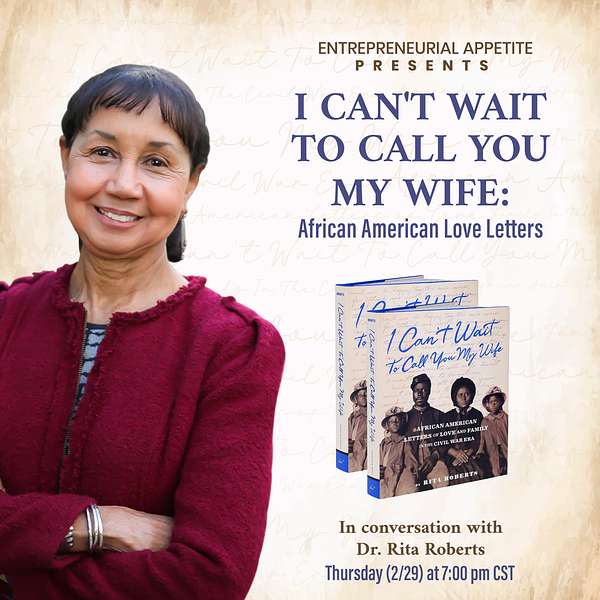

Unearthing the Personal Narratives of African American History: Dr. Rita Roberts on Love, Literacy, and Legacy

When Dr. Rita Roberts recounts tales from her grandfather, it’s like unearthing lost treasures from the annals of history. In this heartfelt exchange, she narrates her evolution from a captivated child to a revered historian, enriching our understanding of African American experiences during the Civil War era. Her book, "I Can't Wait to Call You My Wife," not only showcases deeply moving letters but also serves as a vessel, transporting us across time to grasp the profound connections of love and family that withstood the test of adversity. Her voice adds texture to our conversation, as she unravels how historical documents aren't just artifacts but lifelines to voices long silenced.

Imagine the act of reading - so often taken for granted - as a radical weapon against the chains of slavery. Dr. Roberts guides us through the shadows of America's past, illuminating the defiance and determination of African Americans who wielded literacy as their shield. We delve into the complexities of 'hired out' slavery, the half-hearted dance around abolition in Northern states, and the intense emotional landscape of those who were traded as commodities. Their relentless quest for dignity and the sustenance of family bonds form the crux of a gripping narrative that challenges us to see beyond the surface of historical facts.

Emancipation brought new horizons for African Americans, yet the journey was riddled with trials of identity and respect. The episode reaches its crescendo as Dr. Roberts brings to life Jordan Anderson's dignified refusal to dismiss the wrongs of his enslavement. The conversation ventures deeper, exploring how faith intertwined with the yearning for liberty and how the personal writings of abolitionists revealed their intertwined struggles for racial and gender equality. Rounding off with an examination of racial ideology's lasting scars, this episode is a testament to Dr. Roberts' dedication to preserving the rich tapestry of African American history through the intimate medium of letters—a legacy of individual lives that collectively shape our understanding of a painful yet pivotal chapter in America's story.

What's good everyone. I'm Langston Clark, founder and organizer of Entrepreneurial Appetite, a series of events dedicated to building community, promoting intellectualism and supporting Black businesses. Hey everyone, thank you again for your support of Entrepreneurial Appetite. Beginning this season, we are inviting our listeners to support the show through our Patreon website. The founding 55 patrons will get live access to our monthly discussions for only $5 a month. Your support will help us hire an intern or freelancer to help with the production of the show. Of course, you can also support us by giving us five stars, leaving a positive comment or sharing the show with a few friends. Thank you for your continued support.

Langston Clark:I want to start our conversation with Dr Rita Roberts, who is the author of I Can't Wait to Call you my Wife African-American Letters of Love and family in the Civil War era, and so, before we begin getting into the book, the conversation about this, what I think is a beautiful text, not only because of you know the letters that were written by our ancestors, but like it's just this, the way the book is put together is a piece of art, and so the publishers were wonderful.

Langston Clark:Well, they did a great job. Yeah, they did an outstanding job. And so, dr Roberts, could you just tell us your story before we get into the story of the book?

Rita Roberts:Well, I'm a professor emeritus now. I retired this past June African American history, american history with a specialty in the 19th century history, american history with a specialty in the 19th century, and I taught for over 30 years almost 40 years, at one institution and a few places, a few other places history and also journalism. I taught journalism for a very brief moment because I have my first degree is in journalism. So I came about this book in terms of teaching, trying to make sure that my students were understanding what it was I was trying to convey about the 19th century. It's hard for a 21st century student to really understand the 19th century, and they can't even understand the 20th century, especially mid-20th century. So using documents has been my way of teaching for a very long time and I think it's the best tool a historian can use to teach undergraduate college students and high school students as well. So this book is just an example sort of of how I teach a class, a history class about African Americans.

Langston Clark:So how did you build your interest in history? Was it something that started for you just growing up in your household? Was it like a purely like academic experience? What's your story as a historian?

Rita Roberts:Good question. My grandfather, my mother's father, was very interested in history and he always talked about the past and he would sort of give me a history lesson if I visited my grandparents' home. He would want to know what I was learning, for example in the fourth grade, and I would tell him and then he would tell me you know is a true story, and basically say, your teacher knows nothing. And so he would tell me the true story and I always just thought it was really interesting what he told me. What I learned in school was usually, unfortunately, rote learning names, states, places and I thought it was the most boring. I certainly I aced it.

Rita Roberts:It was easy, but there was no substance to the history and I knew nothing about Black and Indigenous history, and so my grandfather would just sort of no, they were the massacres, no, these were the victims. He would subvert everything and it really piqued my interest. So I always liked history. But even when I went to grad school at Berkeley I didn't intend to stay. I was going to get a master's and then go on and get a law degree, but I just couldn't stop reading, I couldn't stop studying. When I went in the 70s, early 80s, there was such an interest in Black history Finally. So I took my first Black history class in grad school and I just couldn't stop reading, and mainly it was because there that so often what was said in a graduate seminar was something that I just knew from my family, from African-Americans around me, and I thought, well, why is it that they were just finding this out?

Langston Clark:Yeah.

Rita Roberts:And as if it's now known. For example, one of the statements was made in one of my first seminar classes, taught by two professors. One professor said it is now known that there were many Black and Native American. I think he said he may have said Indian, but basically Indigenous sexual alliances or marriages and I thought, my God, it's now known. How do? You not know this, this is known. Black people know this. It was that sort of thing that I thought, wow, a lot needs to be done.

Langston Clark:It's interesting to me that you bring up like your interest in the law and I have a lot, actually I think I have a lot of mentors in the academy who are historians and I always think like historians are interesting because I feel like you all are the most dynamic scholars and I say that because you all can count, like think about all the dates that, like you all do the math in your head oh, this happened in this year, so about 28 years before that do you know? And you just do the math like this in your head. But but then if you think about the law, like the law is all it's historical, because they always reference precedent, right, it's context. Yeah, it's always like they're always looking back and that is so much related to like how I think about the past, how I think about history and what historians do. So I always admire the work that historians do because it's not just looking back in writing. There's much more to it than like, I think, what we see in a finished product, like we have with your book.

Langston Clark:So, also relating to your experience, like I feel like I always encounter some old Black dude who pulls you to the side and is telling you like the real history, right, I think that's like a common thing, right, and like in Black community, like you go to the barbershop, or even it's like I went to Tulsa two years ago, it was actually last year in March there's like this mainstream or more popularized museum of Tulsa that just got opened up in the 100th year anniversary or whatever. So there's a history there. But then we walk down the street and there's old black guys just sitting in the chairs like no, this is what really happened. What we're trying to do is the real thing. So it's just interesting how those things manifest. So now I want to get into the book a little bit, and I know you talked about how you use actual artifacts in your teaching, and so just tell us a little bit about how, the story of you using those letters in your teaching and what eventually became this piece of art, this book, this history.

Rita Roberts:So this book came out of really constant invitations by people in the community, black, white people in the community who wanted me to come and talk about Black history, and they almost never. I don't think they ever gave me a theme. They would just say, obviously during February. Gave me a theme, they would just say, obviously during February would you come and be our speaker? And I turned down many. And then I realized, you know, I really I tended to accept invitations from Black organizations, of course, and one of my first acceptances was with the National Negro Women's Club, a regional meeting in San Gabriel, california, and I prepared a lecture and I thought I bombed, I just think.

Rita Roberts:I did not do well at all, and so I gave a few other sort of lectures and because they gave me these large themes and I was a fairly young scholar and I just didn't sort of connect with the audience, and then I realized if I was going to ever accept again, I would do what I do in my classes and that is use documents. So I started using letters and it made all the difference. The letters are so accessible and I started using letters that had to do with whatever the issue I wanted to teach or wanted to demonstrate to a particular audience. So, for example, if I was talking to a group of black males who wanted to learn more about Frederick Douglass, I'd talk about Frederick Douglass, but I'd use letters he had written to sort of pull people in, and these were Black male professionals.

Rita Roberts:But mainly when I spoke I spoke to a very general audience and so I had to sort of pull letters from different authors, just as I do in my class and with my class.

Rita Roberts:I would just start reading a letter, as the students are coming in for the first day, and they would sort of look like what's going on and I would then tell them this is what the course is about. So for giving talks about African American history, I just thought this is the only thing that's really going to work well, and it did. It worked really well. And then, because I can't be everywhere and give talks all the time it can be time consuming I decided I would write a book and I would focus on the Civil War, since I'm intrigued with the Civil War. I think we're still fighting the Civil War as a matter of fact and so I decided to use the Civil War era and just pull letters from there and then focused eventually I was going to do sort of public-private letters, and then I decided to focus eventually on private letters, and that's how the book came about that it was a matter of finding an agent and a publisher.

Langston Clark:Yeah, the book resonates with me for a number of reasons. One, as I'm reading the letters and for those of you who are listening, when you get the book you'll notice that a lot of what's written here is written in cursive. And so it took me back to my grandmother and we talked about this in the pre-show right.

Langston Clark:My grandmother used to write me letters all the time and I'm disappointed in myself because I didn't always keep those letters Like number one. I couldn't always read her handwriting and it's not because it was sloppy, but like I didn't read, grew up reading cursive as much as, like you know, her generation did, even though we still learned it while I was in school. It wasn't the same, you know it wasn't the same, but the letters my grandmother would write would always be about, like, always deeply spiritual and religious Keep God first. She would like write a psalm or some passage from the Bible in there or something like that. And so I'm wondering if you could share, because I know in my, in my family, experience that we have a tradition of letter writing Like what has letter writing been for you and your experience as a black woman and as a historian?

Rita Roberts:writing been for you and your experience as a Black woman and as a historian. Well, as a historian, letters are crucial for getting in the mind of the letter writer. You can't really understand Abraham Lincoln, for example, if you don't read what he wrote, and what he wrote privately always different from public and are usually because it's more intimate, depending upon the receiver of the letter. So historians use letters as part of their way of writing history, of interpreting history, interpreting the past. For me personally, my husband and I used to write letters to one another and my husband still writes little notes.

Rita Roberts:So we sort of have this communication, this way of communicating that is probably unusual for the 21st century. We don't just text one another.

Langston Clark:And you know I'm gonna steal that. I hope my wife doesn't hear this, because what's gonna happen is I'm gonna start writing her letters and get me some brownie points there, but that's a different conversation. Valentine's Day has passed. Another thing that I thought was fascinating about this book because in the podcast we've read tons of history books and I've never read one where the actual primary source was sort of like the anchor for the text, like it was in there in the text, right. Because I even think, like the way you wrote this book was a very artistic way of writing the book. It's a piece of art not only in the fact of like the way that it looks, but the way that it was written to me is probably the most unique way I've ever read a history book. Written to me is probably the most unique way I've ever read a history book. So talk about the process and what it meant for you to convey this Black history through these Black letters.

Rita Roberts:So you have essentially understood the point of the book, and that is to increase our understanding of African-American history for all Americans, for people, anyone, and it was intentional in that I wanted to convey particular themes. One theme is that African-American experience is diverse, that African-American experience is not a monolith, that all Black people don't think alike, had same experience urban versus rural, north versus south, regional and this is 19th century. Of course, all Black people were not enslaved, and even enslavement, enslavement could be distinct. So I wanted to make sure that we understood that, because to me those are primary themes of African-American history, not being in monolith but being extremely diverse. And the other one is that African-Americans lived, even in slavery, with a sense of purpose and dignity, and I think the letter writers demonstrate that, and so I wanted their voice to be primary, not my voice, and so I selected letters.

Rita Roberts:Obviously, the letters are not representative of all Black people, because most Black people were enslaved and most Black people were not allowed to read, did not have literacy skills, could not read and write.

Rita Roberts:But we have discovered, as I note in the book, that 5% to 10% on plantations knew how to read and write. Whether the slave owners knew it or not. There was this ability to read and write, and so they were able to convey with one another what was going on in their region, whether it was Alabama or in North Carolina. The literacy gaining literacy is a demonstration of their determination to resist the system and to live with purpose and dignity, and we just see it among free Black people, among enslaved people and this is a theme throughout and for slavery. I definitely intended that to demonstrate that family was central, and the centrality of family is a demonstration that African Americans in slavery were determined not to behave and exist in a world of commodification, even though that's what slavery was all about. They were within this market economy and they were traded, auctioned, inherited, sold, which means you're a product you're a commodity.

Rita Roberts:But in choosing family, in choosing a wife, in choosing a husband, in choosing to court, in choosing to parent, they transcended that commodification. They were not dehumanized, which is what so many high school students are taught, I guess, because I still hear it. They were not dehumanized. The system was dehumanizing People who enslaved them were certainly dehumanizing themselves, the enslavers but, they were not dehumanized, they were not simply objects.

Rita Roberts:They were individuals with purpose and tried to attain dignity as far as possible and tried to stay together as family as far as possible, and so what I wanted to do is just overwhelm the reader with this notion of how family was. This means to challenge the system that said they were mostly property and not human, because that's what the law says.

Langston Clark:Yeah, it was really interesting. Something that stood out to me there's a part in a book where you could be enslaved and employed at the same time. Yeah, I've been aware of the concept, but I never heard of it before, and so I think it's interesting where in my research, we talk about Black athletes, right, and so the analogy for Black athletes has been the plantation model for sports $40 million slaves has been used and all of that. And people will say and I think it had been historically more appropriate in college sports. But people would say you couldn't compare college sports to slavery because it's not the same institution. And, granted, I would say it's not the same. But you have these brothers and sisters who are playing and not getting paid for their work. They can go to school, they can move around, but they were Black people who were enslaved, who had that relative freedom, right. Someone might look at it and say, well, that's not slavery, that's kind of like a watered down version. But that didn't mean that your wife or your husband didn't get sold to somebody else.

Rita Roberts:Well, not only that, we need to be really careful about how we want to analogize slavery with modern day situations. If, in doing that, we trivialized what slavery was. Because you do not own your own body, when you are in slavery, you have very few choices. That's what it means to be enslaved. But yes, there were individuals who were hired out slaves, and a lot of widows, white women, who were slave owners, depended upon these hired out slaves for their livelihood. In order to exist, and hired out slavery just kept growing, especially in the urban areas, into the Civil War era, into the 1860. Even so, it's not unusual and there are really good books on hired out slavery to be the manager of a shop, which John Washington was. He knew how to read and write.

Rita Roberts:The slaveholder benefited from that. He got paid very well. Of course, all of the money went to her, his slave owner, not to him, but he had more autonomy. I think we might want to say I don't like the term privilege. This seems antithetical to what it means to be enslaved. So he had more autonomy than a person in the field on the large plantation, so much so that he could go to a church and meet his future wife, but he was still a slave. Yeah, and that's why he escaped. He could have been sold at any moment. If his slave owner died, who knows what would have happened to him?

Langston Clark:Right, he could have been sold to the deep south, he could have been in the field. Total team yeah.

Rita Roberts:Yeah, yeah.

Langston Clark:I appreciate how you weave in all of these different parts of history at the time, black history at the time, through the letters and the context that you provide for the letters.

Langston Clark:One thing also that stood out to me and we didn't talk about this in a preliminary conversation was how northern states tried to get around the abolition of slavery. And so New Jersey, which is where I claim, although I was born in Buffalo, so there's a lot of shout out to places that I've lived and grew up in, so Buffalo was prominent in here, but I grew up mostly in New Jersey. That point about how New Jersey tried to get around the abolition of slavery like really stood out to me. We don't hear that about the North as much as we should and how in some ways they tried to like skirt around the rules and figure something out. It was like a form of Jim Crow Like we know this is. We're still going to just make it harder and harder for you to not be a slave, you know. So I appreciated that you added things like that in the book as well.

Rita Roberts:Yeah, new Jersey stands out because New Jersey never really abolished slavery. You know they did, but they had gradual abolition. So those people who had been enslaved continued to be. They called them apprentices, they did not want to let them go. So New Jersey, you know, last to pass a gradual abolition law because a lot of people made money on slavery. If you don't have to pay for your workers, you have more in your pocket. We see that today. That's why people are paid so low. That's why there's some a few who have a whole lot of money and a lot who don't have any. So many in the North were not interested in abolition and in New York and Massachusetts another example it was the white workers who did not want to compete with slave labor because they couldn't command the salaries. If someone could hire a slave to make their furniture pay much less, for example.

Langston Clark:This is like interest convergence, which is a major theme of critical race theory. Right, it says that progress doesn't happen for Black folks I'm paraphrasing unless it's within the interest of white folks. For Black folks, I'm paraphrasing unless it's within the interest of white folks.

Rita Roberts:And so this goes back to Unless those interests converge, Converge Federal right.

Langston Clark:Yeah, yeah, or intersect, and that was one of those things where I learned it in academia. It was like, oh, I knew that. Like I knew that just growing up being a Black person living life. So something else that really stood out to me was who wrote letters. Something else that really stood out to me was who wrote letters and it goes beyond just letters between husbands and wives, wives and husbands, lovers and what have you? There's friends, there's families, there's lovers, there's presidents, et cetera. So could you talk about the diversity of relationship between the letter writer and a letter receivers?

Rita Roberts:in the book. I begin with the period. The book is divided into three parts before the Civil War, antebellum Civil War and then post-Civil War. And I begin with letters written by enslaved people. One example is a young woman writes to her mother hoping her mother can buy her before she is sold to the Deep South. Her mother can buy her before she is sold to the deep south and her experience would be that she would be sold into what they call the fancy trade. And this was a trade in New Orleans where young women who were of mixed ancestry, more European actually than African, were sold into these brothels, some very young, some very young kids, and raped repeatedly in these brothels. And she begged her mother to try and find means. Her mother had moved to the north and was hoping to buy her to get her out of slavery, but the slave owner decides to sell her to a trader and she ends up in Alexandria, the Alexandria slave pens. The slave traders didn't care who purchased them, as long as they got their money.

Rita Roberts:So, if she was able to raise the money, sure. So she writes to her mother she's able to read and write herself begs her mother to get her out of slavery. And her mother doesn't have the means and can't raise the money. Often they would ask abolitionists to help them raise the money, and her mother isn't able to, and so she is taken by a slave trader down to New Orleans and on the way she dies. So that's one example of an experience. Another example in that very same period is a letter written by Annie Douglas, who was 10 years old Frederick Douglass's youngest, Frederick, and Anna Douglass's youngest child. She writes to her dad and she tells him about how she's learning German. And so you know, talk about diverse experience there in Rochester, new York, and Emily Russell, who I was just talking about, was in Virginia.

Rita Roberts:So this is the pre-Civil War period. And then I write about the Civil War period, various letters. There A woman writes to her husband and asks him to get her out of slavery. They have several children, harriet Newby and he joins John Brown to fight because he can't raise the money. He tries to raise the money, he's not successful. So he joins John Brown, thinking well, this is the only way out. He'll go and get his wife himself. He is killed and the letters are found on his body.

Langston Clark:Yeah.

Rita Roberts:So that's another example. And then you go to the post-Civil War period and just innumerable examples of individuals who are just trying to get their lives together in the post-Civil War period, searching for family. So much is going on then.

Langston Clark:There are some interesting things that stand out to me, and so there are letters translated by enslavers, which I thought was interesting, and there are letters translated by enslavers, which I thought was interesting, and there are letters to former enslavers.

Rita Roberts:Yeah.

Langston Clark:And so like, for some reason, like I don't know why, I would have thought that the enslaver would ever like the perk. Obviously Right, because the black person was likely illiterate, couldn't read or write, and they had to tell the enslaver, like, what they wanted to send to the family member, and they were the ones who sent it. I never thought that would happen, for some reason. But then I really appreciated the agency of people writing back to their former enslavers, like being in the situation that they're in they're free, they're asking for employment, they want back pay for the labor that they did and they want to be treated with respect and dignity.

Rita Roberts:Yeah.

Langston Clark:Could you talk a little bit about those relationships or how you came to those particular letters in your research?

Rita Roberts:So Jordan Anderson is the most famous letter and historians have been using it for years. It appeared in the New York Times in 1866, I think it was. It appeared in the New York Times in 1866, I think it was Jordan Anderson's former slave owner this is post-Civil War asked him to come back and work for him. Obviously, Jordan Anderson did work very hard and he see if I can find the letter. His slave owner tells him that he needs to come back and he can let bygones be bygones. Essentially, I mean, the arrogance of slavery is bizarre, Arrogance of racism is bizarre.

Rita Roberts:So Jordan Anderson decides to take the time to write back to his former slave owner and this is in 1865, slave owner. And this is in 1865, August 7th. So Civil War ends in April of 1865. So the slave owner is finding he has no one working for him and so he writes to him and tells him he wants him to come back. And Jordan Anderson just says very clearly I want to know particularly what the good chances you propose to give to me so evident. He said in this letter we don't have the former slave owner's letter, but we have jordan anderson's letter and he says I'm basically doing pretty well here. So what are you offering? And he says as to my freedom, but you say I can have, I have that. So, essentially, why are you offering me freedom?

Rita Roberts:I am free yeah and he says there's nothing to be gained on that score. So he's trying to figure out. So why are you offering me freedom? I am free. And he says there's nothing to be gained on that score. So he's trying to figure out. So why are you writing to me? But he wants to let him know, jordan Anderson.

Rita Roberts:So I teach this letter as an example of what African-Americans who had been enslaved expect out of freedom. So I call it my lecture was Black Freedom in the Black Mind, because I also have a lecture on Black Freedom in the White Mind, and so Black Freedom in the Black Mind is Jordan Anderson, I want to be paid for all the years that I worked for you and that my wife worked for you. I want to be paid and I will deduct the dental care that you had to pay, but I want to be paid with interest. Talk about reparations. Basically right, he's pretty clear on that. And he says my daughters are called by their first names, they have respect, and he basically implies that my daughters are not threatened with rape and my wife is called Mrs here in Ohio.

Rita Roberts:And he says there was never in Tennessee, which is where he was enslaved, any wages for the Negro, any more than there were wages for the horses and cows. And then he just adds surely there will be a day of reckoning for people like you. So he just has these little snide things, and then at the end he says and say howdy to George Carter evidently another white man and probably a slaveholder and thank him for taking the pistol from you when you were trying to kill me. That's how he ends the letter. Jordan Anderson has no intention of going back, but he's letting this arrogant man know exactly what would be entailed if he were going to experience freedom in Tennessee as he was experiencing in Ohio.

Langston Clark:Yeah, I also appreciate it. In the book, the, I don't want to say this there are people who have a view of Christianity and I'm not arguing that they're wrong for this that Christianity has been used as a tool of oppression and it has right. But what I thought was interesting is like there's a part in a book where it was like like there are people who were anchored in their faith, who weren't nonviolent, who saw like being a Christian is like you fighting for your freedom or you rising up against your oppressor, as something that was noble and in line with their Christian faith.

Rita Roberts:Matt Turner is the best example of that.

Langston Clark:Yeah, and I think that there were some echoes of that in the book. Could you talk about that a little bit and how it came about in some of these letters and some of the history that you integrated into the text?

Rita Roberts:So John Copeland Jr is also one of the few Black men who joined John Brown's group to go and liberate enslaved people in Virginia. I've never been convinced and I have colleagues writing a good book on John Brown now so I'm excited to see what he's going to say. But I've never been convinced that John Brown actually thought that he was going to somehow free all slaves.

Rita Roberts:But I think he believed and this has been said before that he would start the Civil War. And I think he did. I think he was pretty successful in that liberate as many enslaved people as he can. And he is caught and he's going to be executed, as was John Brown in Virginia, and so he writes to his parents and says to them that he is fighting for a sacred cause, this is a holy cause, and he is very, very much a Christian, very religious, the language is very religious, and he is certain that God is on his side. And all of those Black abolitionists, those Civil War soldiers, knew that slavery was the most evil sin and, yes, it had to be exterminated.

Langston Clark:It's interesting the types of relationships between Black folks who were enslaved, formerly enslaved, and white abolitionists that come up in these letters, and one that stands out to me it's Sarah Mapps Douglas, if I remember her name correctly and I can't remember the white lady's name the abolitionist who was writing her back and forth.

Rita Roberts:But Sarah Mapps, douglas, sarah Grimke.

Langston Clark:Sarah Grimke. Okay, so they're going back and forth and I remember he says Sarah was, she was an abolitionist and she was a feminist at the time and she was unmarried and Sarah was having this back and forth and wondering about getting married and so she got some encouragement about she basically got dating advice right. Like it was really interesting that she got dating advice from her white homegirl at the time about like what to do about getting married. And that was one of the letters that really stood out to me because it was different than the letters To me. I know this is a Black history, but really kind of something where the white people in this book and the different roles that they played in those letters, and so could you kind of talk a little bit more about the white abolitionists writing letters in the Black folks at the time who were in relationship with one another.

Rita Roberts:I think Sarah Grimke and Sarah Maps Douglas were family to one another, and so, because this book is about family, I wanted to sort of broaden what family meant or means to all of us, and that there were these potential relationships in which individuals could transcend race.

Rita Roberts:And I think you see it to some degree. I'm not suggesting that this occurs completely, but the potential was there, and I think those two women Sarah Grimke is quite a bit older than Sarah Douglas and both communicated with one another forever, it seemed for decades and they developed a relationship based upon they, like others, developed a relationship that enabled them to go beyond simply the politics and talk about their most intimate details of their life. What's interesting is that Sarah Grimke never marries, and so she's giving marital advice. I don't think she ever dated, to tell you the truth. I mean, this is 19th century, but she's giving marital advice. You know about not being squeamish about having a sexual relationship, because Sarah Maps Douglas is not sure on that score. So to me it says that even in the 19th century, when racial ideology was so rampant as it was in the 20th century and it still is today.

Rita Roberts:There are these possibilities of relationships that are able to transcend race to some degree.

Langston Clark:Before I get into my final question, I want to highlight some of the comments in the chat and in the Q&A. Okay, I will try my best to relay these comments and questions to you in the spirit that the questioner has written them. So one of the anonymous attendees wrote this that they can't recall whether or not you engaged with William L Andrews' slavery and the caste in the American South, slavery and caste in the American South. And this person says I'm reminded of these tears and caste within the US enslavement as they listen and they're describing it as powerful and infuriating and they want to know do you agree that the cast both reified and created intra-racial discourse? So I guess the racial cast that exists within, like light skin, dark skin, is what they're referring to.

Rita Roberts:Is that what they're talking about?

Langston Clark:I think so.

Rita Roberts:You think?

Langston Clark:so. But if you want to clarify, you can.

Rita Roberts:I know William Andrews, william L Andrews, but no, I didn't engage in that text at all. But yes, we should not be surprised that a society with racial ideology so embedded in its culture, this entire culture of American culture, that Black people would not be affected as well. And certainly the evidence is there, whether Andrews talks about it or not, that those who looked more like whites had more advantages generally. And often people talk about elite and privileged and I think those are really problematic terms. We need to realize the degree to which those who were light-skinned, looked more European, may have had some advantages, but they also had a lot of disadvantages. It was, in my mind, much better not to have those advantages in the sense that they could have greater community within the Black community. But yes, it exists. It exists today. We know that Black people some of them, but not as much as it used to be tend to get a job quicker, and of course it is resented and it should be, but that is the reality of living in a racist society.

Langston Clark:Yeah, I want to give a shout out to Angela Roberts, I want to give a shout out to Kimberly Castillo and I want to give a shout out to Kimberly Castillo and I want to give a shout out to Joycelyn Moody, who's here. So Joycelyn is a colleague of mine and I describe Dr Moody as the most powerful Black woman on campus because she's the Black elder on campus. She don't mind me saying that. Who's been where we work the longest and in the comments that she's making in the chat she's been thrilled to be part of the discussion, in part because her primary research is intimate life narratives, especially diaries and personal condolences, and so she appreciates you being here.

Langston Clark:Dr Moody is an English professor. This is right along. I may give her my copy of the book if she hasn't read it already, because I think she'll enjoy it. And if there are normal questions from the audience or comments, I want to ask my final question for the evening and that is if there was another chapter of the book that you would include, what would it be? Or maybe there's a letter that you wanted to include but maybe didn't have enough space for it or couldn't find like the best fit for it in the book. What would that be?

Rita Roberts:Well, there's actually another book, oh, okay, so I cut the book in half. So I decided to focus on private letters. I had my first book, the whole book. The book I sent to the agent was public and private letters. So a lot of letters between abolitionists, many Black abolitionists, a lot of letters between Black abolitionists, many Black abolitionists, a lot of letters between Black abolitionists, and there are just so many. But I decided, in cutting it in half, that I would focus on what I believe is so important for African-Americans to know and to demonstrate, and that is how African-Americans made family central and that they transcended this notion of being dehumanized and being commodified. So I focused on that, and so I'm pretty satisfied with the letters I have.

Rita Roberts:My favorite letter is the one that Laura Spicer's husband wrote to her, and that's at the end of the book, toward the end of the book, in which he writes to her and tells her how difficult it is for him and for her to have found out after the Civil War was over and they had both been sold away from one another and they had children together find out that they were both alive.

Rita Roberts:He had remarried and now he had another wife and children and she just wanted him to come get her and she finds out that he's married and he tells her more than once how much he loves her and that he wants to see her, but that he's afraid to see her and the children because it would tear him all to pieces. The letter is the saddest letter I think I've ever read in my life and actually when I read it to my students they would cry yeah, it's a powerful letter, but it attests to the degree to which African Americans live their lives in a way that allowed for that kind of intimacy, that kind of commitment, that kind of dedication, that tremendous love under the most difficult circumstances.

Langston Clark:Yeah, and Dr Moody did ask another question In your research, was there any same-sex intimacy correspondence? And she says eg, addie Brown and Rebecca Primus or Primus.

Rita Roberts:Not in my work. No, I didn't come across it. Yeah, I do know of those, but no, I haven't. Yeah, come across it.

Langston Clark:All right. So, dr Rita Roberts, thank you for joining us today. Again, this book is a wonderful piece of art, not only in how it is designed, but in the way that you structured the book, and I'm gonna hold mine up as you hold yours, okay.

Rita Roberts:I love the cover it is.

Langston Clark:I love the cover. Yes, if you look at the inside of it, it has letters like all throughout the book, and so you all make sure you pick up. I can't wait to call you my wife. African-american letters of love and family in the civil war era. Dr Roberts, thank you for joining us this evening.

Rita Roberts:Thank you so much.

Langston Clark:I era. Dr Roberts, thank you for joining us this evening. Thank you so much. I enjoyed it. All right, Thank you for joining this edition of Entrepreneurial Appetite. If you liked the episode, you can support the show by becoming one of our founding 55 patrons, which gives you access to our live discussions and bonus materials, or you can subscribe to the show. Give us five stars and leave a comment.