Entrepreneurial Appetite

Entrepreneurial Appetite is a series of events dedicated to building community, promoting intellectualism, and supporting Black businesses. This podcast will feature edited versions of Entrepreneurial Appetite’s Black book discussions, including live conversations between a virtual audience, authors, and Black entrepreneurs. In this community, we do not limit what it means to be an intellectual or entrepreneur. We recognize that the sisters and brothers who own and work in beauty salons or barbershops are intellectuals just as much as sisters and brothers who teach and research at universities. This podcast is unique because, as part of this community, you have the opportunity to participate in our monthly book discussion, suggest the book to be discussed, or even lead the conversation between the author and our community of intellectuals and entrepreneurs. For more information about participating in our monthly discussions, please follow Entrepreneurial_ Appetite on Instagram and Twitter. Please consider supporting the show as one of our Founding 55 patrons. For five dollars a month, you can access our live monthly conversations. See the link below:https://www.patreon.com/EA_BookClub

Entrepreneurial Appetite

The Black Reparations Project Part 2

Use Left/Right to seek, Home/End to jump to start or end. Hold shift to jump forward or backward.

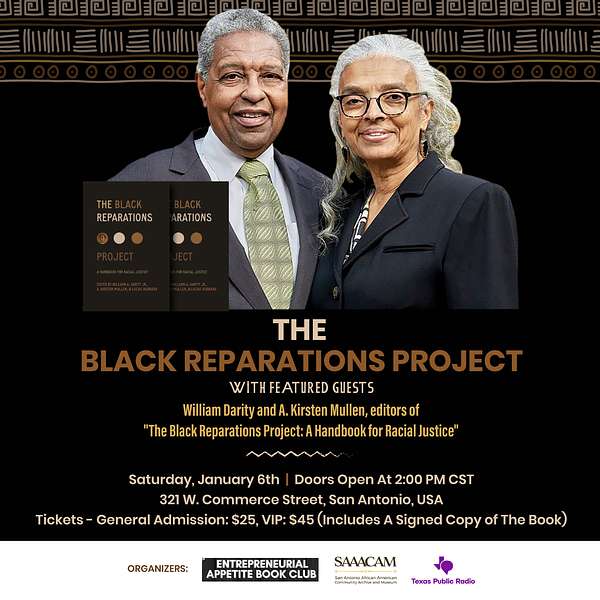

Join us for part two of this two-part series, where we continue our journey as we sit down with esteemed scholars William Sandy Darity and A Kirsten Mullen, the architects of the Black Reparations Project Handbook. Our conversation is a deep and transformative look into the heart of reparations for Black Americans, a topic that unravels the fabric of our nation's history. We traverse the could-have-been world of 40 acres land grants, dissect the insufficiencies of piecemeal local and state attempts at reparations, and scrutinize the controversial HR 40 legislation. It's a dialogue that promises to challenge your perceptions, offering a nuanced perspective on the moral imperative to right the wrongs of the past and the potential to heal a nation through a comprehensive federal reparations program.

In a twist that reveals the power behind the scenes, we pull back the curtain on how media shapes our understanding and collective narrative about reparations. From the intricacies of determining who is eligible to receive reparations to the crucial role Hollywood plays in influencing public opinion, our discussion with Darity and Mullen is a masterclass in the interplay of media, identity, and history. We look at how representations of diverse relationships and social issues in the media can lead to widespread acceptance and change, pondering the possibility for this to pave the way for reparations discourse.

Finally, we reflect on the burgeoning support for reparations among different demographics and discuss the critical support HBCUs need, and deserve, as pillars of education and progress. We talk about closing the racial wealth gap, the tax implications of reparations payments, and the need for unity in the face of a fragmented support system. As we set the stage for future dialogues and action, we close with a heartfelt call to listeners, inviting them to join in the global fight for reparations—a fight rooted in justice, solidarity, and the unyielding belief that together, we can forge a path toward rectifying historical injustices.

Welcome back everyone to the second part of our special episode centered around the Black Reparations Project, a handbook for racial justice. I'm thrilled to have you joining us once again as we continue our conversation with the insightful editors of the book William Sandy Darity and A Kirsten Mullen. This episode is a product of our collaboration with the San Antonio African American Community Archiving Museum, alongside Texas Public Radio, and was recorded in front of a live audience. Before we dive back into the discussion, a quick reminder of the incredible support we've been receiving from our listeners. Your contributions make it possible for us to bring you thought-provoking content and engaging and meaningful conversations.

Langston Clark:If you haven't already, consider becoming one of our founding 55 supporters on Patreon. For just $5 a month, this grants you access to live virtual discussions and early access to episodes. Additionally, we've expanded our offerings with a $3.50 per month tier for those who want early access to content. Your support not only fuels our podcast, but also plays a crucial role in our philanthropic efforts. As a reminder, I'm proud to co-found and endowment at my alma mater, north Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University. Thank you in advance for your generosity. Now let's pick up where we left off in our exploration of the Black Reparations Project. This is part two of our enlightening conversation.

William Darity:So I think chapter six of the Black Reparations Project is a chapter in which we discuss other instances of reparations and what we can learn from them in terms of the development of a reparations plan for Black Americans and some US slavery Also did a back of the envelope calculation. If the average home is on.2 acres then it's five homes per acre and so if somebody had received 40 acres of land, if it was suitable for residential construction, then it would be no no no, no Well you said.2.

William Darity:40, it would be 200 houses, that's right 200 houses.

William Darity:It would be 200 houses and on 160 acres it would be potentially 800 houses. So 40 acres is not trivial either. Okay, so yeah. So I think the final thing we'd like to do in our conversation today is talk about the other detour from true reparations. Now Kirsten has talked at some length now about the idea of local reparations or state reparations, and we argue that that's a detour away from what we might refer to as pure reparations. But there's another detour that is in the mix, which is HR 40.

William Darity:Even if this legislation were to pass Congress, it's highly unlikely to deliver true reparations. In fact it could undermine the entire project. And even if the president appoints a commission instead of having Congress appoint a commission, it will not give us true reparations if it is modeled after HR 40. So HR 40 calls for the creation of a US Congressional Commission to study and develop proposals, and we don't intrinsically object to the idea of having a study commission as a prelude to the development of a full-scale reparations plan. If we think about the case of Japanese Americans in the United States, the introduction of a reparation scheme for Japanese Americans was preceded by a substantial and significant report that was prepared by a study commission. However, we think HR 40, in its particular specifics, will not provide us with the type of comprehensive reparations program that we need and merit in the United States. In particular, it offers little direction as to how to proceed, so reparations could end up being defined as anything from an elaborate apology to the endorsement of piecemeal and woefully inadequate measures, like something like the Vermont effort that invites white people to donate cash to black people who sign up to receive it, or the Evanston Illinois program that has so far made available a mere $400,000 to compensate black families for five decades of housing discrimination.

William Darity:But even worse, when HR 40 emerged from the House Judiciary Committee markup session in April 2022, it contained numerous structural flaws. Among other things, the commission would be exempt from the Federal Advisory Committee Act, which ensures transparency in the form of hearings, public hearings, public agendas, periodic reports on the part of the commission, and so this commission could proceed completely behind closed doors until the point at which it issues its final report. Oddly enough, while the commission has now has provisions for 15 members and originally, when John Conyers introduced it, there were only seven members that were designated for the commission Now it has 15 members, but it's peculiar because only seven of the commission's 15 members are required to constitute a quorum, so that's less than half of the members. And the administrative director, who is not a member of the commission but would be appointed by the chair and vice chair of the commission, would have the authority to appoint six of the 15 members, choosing them from so-called major civil society and reparations organizations. Now we know who this is it's Narcan and Cobra. Okay, so that's the story They've written themselves into the HR 40 legislation.

William Darity:No elected officials would be allowed to serve and members would be able to earn salaries as large as $172,000 a year. So here's the potential outcome an obscure, unrepresentative process in which co-optive members reach an unsatisfactory result, potentially discrediting the entire concept. So, as we said, a proper reparations program should rest on four pillars. There is nothing in HR 40 in its current incarnation that will ensure that the conditions of the four pillars are met. It will not deliver reparations for black American descendants of US slavery and at this point we argue it should be scrapped. America deserves legislation based on strong moral principles. A congressional mandate is needed to guide the nation in the payment of a debt that is now 159 years old. So I guess we will complete our remarks, and we would love to have a conversation with you all about your thoughts, questions and concerns.

A.Kirsten Mullen:Thank you so much. Let's give it up for our esteemed authors. So this is how we're going to do questions. How many of you have seen Showtime at the Apollo? I am not the Sandman, but I can be the Sandman and push you right off the stage. There are rules to this question and answer. Rule number one no pontification. We want a question and that question needs to be one sentence long. If it is any longer than that, I have State Representative Barbara Gurvin Hawkins and she has shown me how to shut it down. We will shut it down because everyone has questions. So that's the rule. Are there any questions about the rules? All right, so I'm going to have this mic in my hand and I'll start playing a tune. If you start pontificating, you can go up to this mic. Thank you.

Speaker 5:Will you please begin with your name? Okay, yes, my name is Sidney Smith and you spoke in depth from here to equality about the freeways being built in the 50s and 60s, and my grandmother-in-law was one of the victims in Miami, Florida that you spoke in depth about. That was pushed out of Overtown. She had a thriving business in Overtown. So now the Biden administration is coming in and they're saying we want to reconnect communities. In other words, what's the question, sidney? Right?

Speaker 5:That's what I'm getting to. So, now that the black people have been pushed out, now they want to reconnect gentrify communities to central business districts and I just want to know what your thoughts are on that.

William Darity:Well, I think we've experienced that in our own town in North Carolina, where the highway was run through the Haytide district and destroyed the business district there and for many years the downtown section of Durham where those businesses had been located was like and just boarded up. Yeah, it was wasteland. But now downtown Durham is in a revival and the revival is affluent white people for the most part. Absolutely, that's true. So the pattern that you're describing is not unique to Texas cities. It's a nationwide trend and we don't necessarily think that the way to handle this is to displace the folks who have moved into these communities, but we should be able to provide the victims of this process with the resources to make the communities where they are currently living as high a quality as they desire.

A.Kirsten Mullen:Thank you. Side note the city of San Antonio did apply for that grant. If you guys don't know that, to connect downtown back to the East Side, attorney White.

Speaker 7:Oh, thank you, Doris White, excuse my throat. Sixth generation Texan. I'm the descendant of blacks who were brought to Texas from Mississippi, alabama, pennsylvania, georgia without their consent, as enslaved people. What is your take, dr Darity or Dr Mullen, on the black farmers' role in reparations? In terms of how do you deal with the black farmer?

Speaker 7:So much land has been taken from black folks, even those who managed to get whatever few acres they could get. How do we build it? And I must give my plug for my ancestors who were in Southeast Texas, in Fort Bend County. My roots are in Fort Bend County, so I knew about that massacre. My roots are in Brazoria and I, my mother, carefully tended 16 acres of land in Brazoria passed down to her from her great grandfather, who was 16 when he was freed and managed to get a farm, and we've held on to it and I'm holding on to it. I told my kids I don't care if it's just one acre, don't let the state of Texas get this land, because my people worked so hard. But how do you factor the black farmer into your economic pattern and your economic solution?

Speaker 4:You know I think the plight is similar across different communities of black people. There were a small number of black farmers who did receive some compensation this was the lawsuit that was filed against the Department of Agriculture but all of those payments have not yet been made right and many, many of those individuals have died and the federal government is, you know, taking its time trying to figure out, well you know, which of their descendants should receive any reparations, if any. I think, ultimately, these are decisions that can only be changed when we change the faces of our legislators. I say to everyone start locally it's not just a question of who's in the White House and who's in the Senate and the House but work locally as well to find individuals who may not look like you but whose values, who want to see freedom, who want to see I mean, democracy almost has gotten a bad name these days but who want full citizenship rights for black Americans and some of US slavery. We have to be active and we have to make our voices heard.

William Darity:Do you want to add to that? Well, I just want to say that Doris White and Steve Soares, a fellow alums of Brown University, and I didn't realize they were in, so I'm gonna tell you about that. And actually, doris, I didn't know you were from Senator.

Speaker 7:I know you can't see me saying wait over here.

William Darity:Oh, okay, yeah, I can't see you, but I think one of the issues you're raising, though, is whether or not we should tailor reparations to the specific histories of particular families, and we think that that's too difficult to do, and so we've consistently taken the position that the reparations payments should be uniform for all eligible recipients. But that is an important question, because you could make the argument that there are atrocities that were inflicted on particular families that other families may not have experienced. I think we want to avoid the question of trying to make a judgment about who deserves more, who deserves less, and so we've gone the uniform payment route, which may not fully compensate families that have accumulated land that had that land seized from them or taken away from them.

A.Kirsten Mullen:Yeah, Thank you Next.

Speaker 8:Hello, my name is Betty Williamson and I have a question concerning the self-identification. I have often thought about reparation and that's why I wanted to be here today to just kind of hear what your thoughts were on it. And one of the things that I constantly think about is that how would that happen? Because there's so many people who have passed, you know, as white, you know, and that kind of thing, and I definitely look at Henry Lewis Gates finding your roots. You know a lot, and there's a lot of white people that they find out that they have black people in their family, you know, and that kind of thing.

Speaker 8:And I have always said that if we go down that route, as far as using identification, you know that kind of thing, it's gonna be more white people, right, who benefit from any reparation payments than black families. Because of historical records, we can't find them, but they can, you know, and that kind of thing. So my question is how did you come up with a minimum of 12 years of self-identification? Because to me, in my mind, that's not enough. 12 years is not enough. So that means that if we just do 12 years, that distribution of whatever it might be is still not going to benefit, to make sure that the reparations get in the hands of those who it should.

Speaker 4:I'll start. I mean, I'll say I take, we take your point about the 12 years and we actually increased it to 12. It was 10.

William Darity:It was initially 10.

Speaker 4:And it's a bit arbitrary, you know that's two senatorial terms, you know which is the 12 years. But you know you may recall we talked about two criteria for eligibility. The identity standard is big, you know. These are if you've lived as white, if your legal documents say you're white, you would not be eligible, not by our criteria.

William Darity:Yeah, one of the things that we thought about was the way in which people self-report their race in the census. Right. You can make that public information. I presume that people living as white typically self-report their racist white and they will continue to do so until there is a monetary advantage to declaring that you're black, and so that's why we are using the 12 year figure to preempt the possibility that individuals will just decide tomorrow that they're gonna self-declare themselves to be black so that they can get their hands on reparations that are not due to them. We also think that individuals who passed or whose ancestors passed are probably living as white and will self-identify as white. But if you don't think 12 years is long enough, we could make an adjustment on that. But we would also have to have a proviso that the children of individuals who qualify also would qualify, because the children may not necessarily have reached a point in life where they could declare what their racial identity is.

Speaker 4:But you also asked about this question of being able to conduct research on your own family's history, and for our purposes you need one ancestor.

Speaker 4:You don't need to know your whole lineage, but say you believe that you are the descendant of an enslaved person. And you are aware of an individual who was alive, say, in 1860, but did not appear in the I'm sorry, who was alive in 1870, but did not appear by name in the 1860 census and was old enough to have appeared. So someone who's at least 11 years old in 1870, you have then kind of negative proof that this person was probably enslaved. But the other thing too and I do suggest that you I don't know if you had a chance to read Evelyn McDowell's chapter many, many finding aids have been developed now for researching genealogies, and it is not the difficult, impossible seeming task that it once was. But, as again I'm saying too, we believe that the federal government should make available this kind of expertise free of charge to anyone who attempts to make the claim. So it would not be a burden that the individual would have to bear to prove their eligibility.

A.Kirsten Mullen:Thank you. Next, lee Wright.

Speaker 9:Hello Lee Wright, so I'm gonna ask my question first and then give a bit of context, so I don't get in trouble with Ms Deborah.

Speaker 9:In your research, what did you discover in regards to the role that local, state, national media and Hollywood as well their role in shaping the narrative around reparations and therefore the hearts and minds of public opinion? And the context out is that one of the organizers, him and I, had a chance to go to Tulsa last year and we were on Greenwood and we were directed by the descendants of those who were victims of the Tulsa massacre. They directed us to one museum that spoke to the experiences of their descendants. At the same time, there had been constructed by the city another museum about 10 minutes away that perhaps shared a different story, and so you're looking at a community of people that are getting two very distinct narratives around an incident, and so again, my question is what role has local, state, national media, perhaps Hollywood, played in shaping public opinion around reparations and what role do you see those institutions playing in the narrative as it pertains to reparations for African Americans?

Speaker 4:That's a big question. I think it's really important to not to use a blanket, give a blanket answer, because all these groups have their, these entities, especially the media entities, have their own agendas. But I wanna speak just briefly to our little bit of a brush with the Hollywood story. So I knew you were gonna go there. So a couple of years ago, sandy was invited to participate in a project by a group called PopShift. We'd never heard of them, but these are the players at Hollywood, these are the directors, these are the executive producers, these are the backers of the media that we all consume, and Particularly advertising media, especially advertising, but not only advertising. They also are involved in plot lines in rom-coms and soap operas and westerns I mean, you name it.

Speaker 4:It's incredible the kind of influence that this group of people have, and one of the examples that they gave about the kind of work that they do was around the whole question of the designated driver, which is a phrase we all know, and the reason we know that is because it's on television.

Speaker 4:Probably some of these individuals' own friends and family members had either been the victims of drunk drivers or had been themselves drunk drivers and they had seen research that suggested that if you simply have someone who will take responsibility for staying sober at a group event, then the number of fatalities and injuries decreases tremendously, and so they seeded that idea through hundreds of TV shows. I remember seeing an episode, so I began looking for them. After we met with these people An episode of friends, an episode of living single Girl. Who's gonna be? I wanna get my party on. Okay, it's your turn. You be the designated driver. And in fact, the numbers of fatalities and injuries decreased by something like 43%. It was successful. They did away with the stigma of the party pooper, you're responsible, you're looking after your friends, you're being a good citizen. So they were talking to us. I mean, it took us a while to figure out.

William Darity:What they really do. What did they want from us?

Speaker 4:And they were talking about. How would you talk about reparations to groups and what are the hot button issues? So the other example they gave was more awareness of same-sex marriages. And the moment they said that, I thought, well, yes, we don't watch a lot of TV. We love, I love TV. We don't have time to watch much of it, but when I do, I'm struck by the numbers of same-sex couples Eating Cheerios or on a yacht, on a Vikings cruise.

William Darity:So their task is to normalize certain types of behaviors. To normalize certain types of behaviors or activities.

Speaker 4:And so, after we had a series of a whole day long event with them on Zoom, we began to see more black and white couples on TV and I said okay.

Speaker 4:So was it takeaway that they got that white people will accept reparations if they get half. It's like, wow, that's deep, right, that's deep. Are you all familiar with the Osage tribe? Yes, I mean, raise your hands if you know anything about. What was the movie Leonardo DiCaprio? No, no, no, you know.

Speaker 4:This is a situation where, you know, this tribal nation was marched from their homeland, I'm gonna say in Indiana, but no, no, from.

Speaker 4:They were marched to Oklahoma. Actually, I think they were put on boats and went to Texas and then they marched up from Texas, but anyway, to land that they, you know the federal government thought was worthless, you know craggy, unarrowable land where perhaps, at least in some people's minds, they would die quickly. You know, done, and many of them did, because it was a hard scrabble life. But, like the case of the white family that Sandy described, that benefited from the Homestead Act with their land grant in the panhandle, after some years, oil and gas were discovered and white people said, darn, that wasn't supposed to happen, that wasn't supposed to happen, they should be gone. They don't deserve that, we deserve that. And they married into the tribe, divorced those native people and, in many cases, murdered them and became the owners of that land. So I don't know. I mean we've not had a chance to talk with the people with pop ship to see if this is the idea, but yeah, well, the question is people are struggling with.

Speaker 4:How do you, how do you make this palatable?

William Darity:The question is are they viewing the normalization of interracial marriages as then as a step towards reparations, or are they thinking about some other objective altogether?

Speaker 4:Yeah, it's not clear. Not clear, yeah, it's not clear.

William Darity:But yeah, so the media can play a role. They're very involved, they're very involved.

Speaker 4:But to what end? Is not clear.

William Darity:We have to be careful about what the role is that they're playing. Yeah, yeah, thank you.

Speaker 11:My name is Gary Houston. Hello, here it. Hello, kirsten, regards to her, god, oh my God, this is so amazing. Yes, four years. Yes, wow. My question is something you've referred to a little bit earlier, that's, given the backlash among state legislatures nationally to diversity, equity and inclusion, and what that will likely lead to as a suppression of your concepts, as well as the New York Times 1619 project and and lots of others in that direction, what would you project as the role of historically black institutions, of HBCUs, especially the private HBCUs, and promulgating these ideas if they're going to be suppressed by state funded institutions? The other, the other question is perhaps a little less significant, but I'm curious whether you feel that Nicole Hannah Jones was treated fairly in that Duke controversy a few years ago.

Speaker 4:I know this. Unc, chapel Hill. Yeah, no, no, no, no, no, not Duke.

Speaker 10:But, well, that's right.

William Darity:Yeah, yeah, in your neighborhood, yes, and not not to absolve Duke in a right. Well, that's right.

Speaker 11:So of course it was in your neighborhood, but I just wonder if you have any, any insights or insight information you'd like to share with us on that episode.

William Darity:Thank you, Well, I think this is. This is a really compelling question. I'm not certain if HBCUs necessarily actually have the degree of independence that would enable them to act any more freely than other academic institutions, or their students act any more freely or independently than students at other academic institutions. You know, a movement a successful movement for reparations in the United States, since, from our perspective, it will require congressional action, will require a sufficient proportion of the US population, black and white, to be supportive of it for it to come about.

William Darity:And one of the promising elements from my, from our standpoint, is the. Is the? Is the the evidence that there has actually been a change in attitudes. If you go back to the year 2000, a survey that was conducted by Michael Dawson and Ravana Popov at the University of Chicago, a survey on American attitudes towards reparations, found that 4% of white Americans endorsed monetary payments as reparations for black Americans. At the beginning of 2023, a survey that was conducted by researchers at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, found that that proportion among whites had risen closer to 30%. I think it's that change in attitude which has also triggered this reactionary response against truth telling in American history. But that's where the fight has to be waged, and I'm not sure it's a fight that can be waged exclusively by HBCUs. It's got to be waged by a much broader faculty all across the country, because universities are under assault in this context. Absolutely, I mean that same poll found that nearly a majority of white millennials.

Speaker 4:Support monetary reparations for black Americans since the US labor, which is huge, which is huge. You know I thought you were going to say something about. You know just how dire the economic positions of HBCUs is. Yeah, well so.

William Darity:So I've done some work with one of the congressmen from Texas. I'm sorry You're in a prayer. No, no, he's from.

Speaker 10:Houston District adjoining.

William Darity:Where is this? Well, harrison County Harris.

Speaker 4:County. Yeah, yeah, so parts of Houston and yeah.

William Darity:So so he approached me to talk about the question of, of, of what should be done about the financial status of HBCUs, and so I began to work on developing a plan for HBCUs, began to work on developing a plan where, if, if, private institutions wanted to engage in some sort of act of, of racial equity, what they could do, particularly the banks, is they could build the HBCU endowments so that they would be at a level that was comparable to peer, predominantly white institutions.

Speaker 4:So these are some examples.

William Darity:So, if you were thinking about the state of Louisiana, I would have paired Dillard University with Tulane, and we would have sought to build Dillard's endowment to a level that was comparable per student. And then there is, of course, the issue of whether or not these institutions would have had more students had they had a better financial history, and so that's something that you might want to factor into the analysis. I paired what is it? Texas Southern with Louisiana State and then University of Louisiana with Texas Southern with which other Texas school them?

William Darity:Right, yeah, no, no, texas Southern with Louisiana State. Okay, because they're state schools and they're both land grants.

Speaker 4:That's right, that's right, and so on.

William Darity:And so that would be the way in which you could do some sort of matching. And now there are going to be some states where it would be more difficult to identify a single matching partner. But Louisiana is pretty easy because they're not a large number of HBCUs there. Our state, north Carolina, has 11. Probably, yeah, yeah, has the most, I think. And so which school to match it with might be a more complicated issue. But definitely I'm concerned about the question of finances. But in the absence of that type of endowment, they really don't have the political independence that would permit them to perhaps take the leading role in this charge. When we first started doing work on this issue, we thought that the colleges and universities would be the leading edge, because there were a number of them that were doing this kind of self study to identify their own complicity with slavery and the like, and we thought well, you know, it makes sense that they would become the leading edge of a reparations effort.

A.Kirsten Mullen:But that's not at all what happened. We were mistaken. We were mistaken, thank you.

William Darity:So I don't know if that answers your question, but that's our struggle with it. Yes, yes.

A.Kirsten Mullen:Thank you so much. We have a question over here, mr Kierkendall, and then we'll get to you.

Speaker 10:Great, thank you. Thank you, you know, as a state representative. Oh, barbara Gervin Hawkins, state representative for District 120. You know, the issue of reparations is big in terms of how we move forward. What I'm concerned about is that unless we identify a uniform eligibility, population that's eligible and a structure that is woven into some of our existing structures and let me kind of share that with you when we speak of reparations, we're talking about trying to locate descendants and things like that, and I'm concerned a lot of people will be left out.

Speaker 10:I would ask this question If our ultimate goal is economic advancement, let's not look at it in a narrow fashion, let's look at it in a broader fashion, whereas we're looking for economic prosperity for African-Americans in general. So if we were to do that, why wouldn't we look at strengthening our universities, our HBCUs? For sure, because what I've seen at the state legislative level is that our universities are suffering because they do not have the state resources. We look at our UT, we look at our AM systems. Those colleges that are under them are not getting even their equal match. For instance and this is specific Prairie View has an opportunity for an $18 million federal grant. That will up to $18 million that needs to be matched with the state. For years the state has not matched it. Finally, I was able to get that done this year, where they will get there for an $18 million match. But there's been a challenge, and I think all of our universities, particularly our HBCUs who's suffering from old facilities, who's suffering from being landlocked, things like that and having a plan through reparations, because when we focus on individuals, we're not strengthening the systems. That's truly going to prepare our folks to have the capacity to be able to make sure that what we're trying to do is sustainable.

Speaker 10:So for me, we've got to look at our systems and how we strengthen those systems through the federal mandate. That's one, because no doubt we have to go federally, because state to state, as you well know, whoever that legislator's body is is going to determine what things they're going to be. So I'd like to pose that question in terms of identifying those key systems and how we modify and enhance them so that they can be sustainable and they can be independent and is not tied to this bigger system who still want to suppress them. That's one question. The other question is looking at holistically if we're looking for economic success among African-Americans, and here's a simple resolution for you.

Speaker 10:If on your birth certificate it shows African-American, black, negro, whatever the name, is okay that we kick into a 25-year federal income tax abatement where you pay no income tax for 25 years. We have a set period of time. The employer can be the verifier because they're looking at your birth certificate and your credit code data, which means the federal level doesn't have to hire a whole new division. So we're looking at number one keeping the money that you earn. As one spoke in the will, another spoke would be how we deal with retirees and another spoke would be how we deal with the different populations as we identify. I'm concerned. If we don't have specificity in this, it will never happen, because everyone will say, well, if you gave it to them, why didn't you give it to those over here? And now we're having infighting and we won't be able to move the ball down the field.

Speaker 10:So for me, how do we develop this uniform system of payment, identification and eligibility that I think has to be tied to a systematic approach?

Speaker 4:So I'd like to start with just two pieces of this. There's a lot here. There's a lot here and your one question.

William Darity:And there's a lot we agree with and disagree with.

Speaker 4:So the first point I'd like to make is that 40% of black Americans don't make enough money to even pay taxes.

William Darity:That's right. Yeah, okay, so that's not going to lift, you know low wealth white people out of poverty. Our objective is not just to close the income gap.

Speaker 4:We're trying to close the wealth gap. Two different things wealth and income. You know income is what you earn through your labor's. You know it might be a daily check, it might be two weeks at a time, it might be a monthly check. Wealth, on the other hand, is the sum of your assets. We're talking about things like, you know, residential real estate, but commercial real estate, your retirement plan your retirement plan yeah, stoxyn bonds, Anuity stocks and

Speaker 9:bonds.

Speaker 4:This is what black Americans don't have in the main and that white Americans do have, but taxes is not going to do it. You know, yes, I think there are many, many, many black people who could benefit from not having to pay taxes for 25 years, but at least 40% of all black people out of that solution.

William Darity:And in our plan the reparations payments are tax-free.

Speaker 4:Yes, Okay. So let me continue, Hold on, Hold on. So I also wanted to speak to this question about specificity. You are correct, Specificity is 80% of the picture.

Speaker 4:When you look at the example of Japanese Americans now we're talking about, you know, families that were incarcerated during World War II because there was a tremendous amount of race-baiting taking place, yellow fever and American politicians, especially in California, insisting that Japanese Americans were colluding with Japan against the United States. To this day they have never found a single case where that was taking place. Interestingly, there were many Italians and Germans who were complicit, but they were not interned. You know, legislators said well, we can't, these Japanese Americans have inscrutable faces and we can't really tell when they're, we can't really determine when they're telling the truth, so we're just going to put all of them in concentration camps, you know, in remote places. So initially Japanese Americans were very divided. Actually, I would actually say initially they're still divided. They receive reparations and they're still divided. I don't think that the receipt of reparations is somehow going to, or the possibility of reparations existing is going to somehow magically erase these divisions. But there were Japanese Americans who did not think that any money should be accepted, that it would be.

William Darity:That was also true of Holocaust victims, of Holocaust victims, that it would be shameful, it would be disrespectful to them, to their ancestors.

Speaker 4:There's no amount of money that could make this right.

Speaker 4:You know Fredric Douglas, famous. He said you know, yes, that's absolutely the case, there's no money, but let's, let's do something, you know, let's. Let's not just you know, let's not just say, oh well, you know, since we can't do what's right, what we can't do, what justice requires, then we'll do nothing. Now, interestingly and I speak because we about Japanese Americans, because we have come to know John Tatechi, who was the executive director of the Japanese American Citizens League, and it's very interesting all of these, these synergies across these organizations. So they and this is something that the 1970s and 80s, they were organized across the country in 100 chapters, modeled after the NAACP, and in fact, their legislation was modeled after HR 40, right, but with some very important distinctions. Right, no HR 40.

Speaker 8:No, sorry, just the other way around the other way around.

Speaker 4:Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, we don't have the time. It's gonna have to be right, right, yeah, because we're now what? 30 years on with HR 40, but anyway. So when 40 years was, so when, and they decided they were gonna put it to a vote, you know, do we? Are we gonna have money reparations? Are we gonna? Are we gonna? Are we gonna fight for money reparations? Are we fighting for an apology? What are we fighting for? And they put the vote to the members across these 100 chapters and the vote was no to money reparations. But the individuals who were in charge said hell, no, we're gonna get that money. And so they suppressed the vote. They suppressed the vote across their own members and they fought for the money and got it.

Speaker 4:They, they, they, you know, and the and the amount of money they received. They just picked it out of the air. No one had done any calculations to look at specifically how much property had been lost, what the value of that property was, and to calculate the interest. You know, at some point they thought we should get a million dollars per person, and I think it was Edward Brooks who said I can't, I can't sell that. You know, we need something that's realistic. They bought $50,000, $25,000. And I think the figure they settled on ends up being what a flat fee and something like $15 per day, something like that approximately. I think the longest incarceration was under five years, and so individuals received $20,000. Now, initially, the plan was to provide reparations for every Japanese American in United States, whether they've been interned or not, cause they were like they were Japanese Americans who were not interned.

Speaker 7:Right.

Speaker 4:Right. But the United States also interned Japanese people, japanese descent, who were in Mexico, who were in Peru. They scooped up those people, kidnapped them and interned them yes, in your name. This is what our government did. And JSL WS American Citizen League said all of these people should be compensated. But the members of Congress said I don't think we can get a bill passed for these non-American citizens. You're gonna need to kind of put them aside and maybe later down the road we can try to get something for them. And in fact, that's what happened. They received a much smaller award, but there are efforts underway right now to get their award, to get them an additional award, these individuals who are from other countries. So the question of how do we, how do enough people come together to make this happen, I think is really important. We're not political strategists. The work that we have been doing is trying to provide the research, to kind of create this blueprint, to talk about how it could happen, what the key back and we're just good people.

A.Kirsten Mullen:Plus, we tailgate with the continental breakfast, so you can come and park at lot one and have continental breakfast with us and then march with us. However, you need to sign up because we wanna make sure you have enough food. We have enough food, so go to saycamorg to do that. And then our film series starts on January 26th at the Little Carver Our film series. This is our third year, fourth year, first year of doing our Black History Film Series and this year we have a film every month. The film in January is Gaining Ground and the panelists will be Black Farmers. So we were talking about Attorney White, you were talking about Black Farmers in the Land. It's an amazing film, amazing opportunity for you to come and listen to our farmers and what they're doing to still feed our nation and try to feed their families and how they are fighting literally to keep their land. So please come free of charge January 26th, 6.30 pm at the Little Carver. And then on January 27th if you haven't heard now, you know that Saycam closed on the purchase of the Crest Department Store and Grant Department Store on East Houston Street right before Christmas, and so we will have a community charrette, on January 27th at 11 am to talk to you all. Well, really, to hear from you all about what it is you want people to walk away with when they visit and experience Saycam downtown. So it's super important for you, for us, to make sure that we hear your voice.

A.Kirsten Mullen:January 27th we again ask you to sign up on our website to attend that. On our website it says it's gonna be at the Carver Branch Library. We have to move it from there. So we're looking at moving it to Overland Partners. But I tell you what if you sign up, you will get an email with the new location and, who knows, if we've gotta do a couple things in the building, we may actually have it in the building. So that's what we're hoping for. But anyway, january 27th, we want to hear from you. Thank you all so much for supporting our very first event. And here is Dr Clark.

Langston Clark:Real quick. Just wanna do a shameless plug for my podcast, Entrepreneurial Appetite. We do monthly discussions like this with black authors and black entrepreneurs and have been partnering with Saycam for years to do these live and in-person discussions. So if you have your cell phone you can type that in your Apple podcast or wherever you listen to your podcast and listen to our show Entrepreneurial Appetite.

A.Kirsten Mullen:Thank you, Thank you, dr Clark, thank you all. Settings and our Eren cosine.

Speaker 12:I think Kristen and I can probably put away what we don't need yet, just because last time I didn't have a mic to capture laughs. So I kind of want to like leave the two that are out just like hide them or something. I guess just one of them goes back and I need like a standing, just one solo mic, and then this is going to turn into our stage. Yeah, of course that's a great conversation. Yeah, a little cold in here though.

Speaker 1:I was freezing. Yeah, I was popping up and running around and it was like kind of balanced.

Speaker 8:How are you feeling? I think it was good it's good, it's good.

Speaker 12:Ah, that's a hi.

Speaker 1:One of these can go, yeah one of those can go for sure. No, buddy.

Speaker 12:Okay. One of those can go for sure.

Speaker 12:What do we want to keep for the? Don't tell students. Well, let's talk about it. I was thinking I'd like scooting the chairs back and then getting rid of the plants and then getting some radios and just like staging radios. Thank you, you're all right. Thank you, yeah. Yeah, you're welcome, go ahead, go ahead. Oh, but that radio and stuff needs to go. We'll add radios and stuff. Do they give you where to keep the chairs and stuff? Maybe it's just a bunch of radios, like on tables. I like that, so we can go, get all the classic radios and set them up Like one of the black four foot tables and then have these little tables, yeah, and then get rid of the chairs, or what do you think?

Speaker 12:I think we should get rid of the chairs unless it's like a fancy looking chair, cause you know they don't really add anything and I'm going to push the things back and bring chairs up. Tickets are with comps. They're already at 100. Nice, but it's like at 93 without comps. I have to find the TPR camera. It's in this building. I feel like shit. Yeah, we're about to do my makeup and stuff. I have to have mine real quick in the dark. Yeah, it looks good.

Speaker 12:I have your eyeliner up there. Oh shit, I was like what did I hurt with my eyeliner? I just ended up getting it on. I was like what do you think about the microphones? Like hiding them? I think if we have them out, they should be like by these podium things. Alfie always used a different microphone, though Is that like something he brings, probably? I might be like a more sensitive one.

Speaker 12:I thought I did not know. Okay, I'm going to start moving the chairs. Oh well, she has all her shit there, oh my god. Keep getting emails about student loans. I'm never paying them. We got like time. Well, I finished all the creep side stuff.

Speaker 1:Our manager was wondering if it was possible to get a picture of the guests in front of this once the book signing is done. We weren't sure how long we would be here.

Speaker 12:Yeah, yeah, yeah, that's fine Just in front of the TBR logo. Okay, we might move some of this stuff. Oh, that's our food court, thank you. Yes, of course, thanks for being here. Amazing, we appreciate it. See that something is going on with that. Look, when you moved it, oh yeah, it's breaking.

Speaker 4:It's like here E elements are that you need to make it happen. I mean, we often think about how, in 1850, few people probably thought that slavery would ever end. That's true, but there were abolitionists who were working on that every day, writing, making petitions. It's interesting. One of the things that we learned in our research is that, up until 1830, the majority of the abolitionist organizations in this country were in the south Well, black and white people, and what happened was at a point when things just became Just outside the white southern abolitionist almost all is were repatriation.

William Darity:Yes, their ideas was we're going to send all these black people back to the continent.

Speaker 4:That was the plan. Abraham Lincoln was in on that as well. But, yes, but even they were silenced, right? You know these individuals were ostracized, threatened, murdered. They moved to the north or they just became quiet.

Speaker 4:You know, similarly, you know, when I was a student, louise Gary, you know I was part of the African Liberation Support Committee and we were fighting with many, many people around the world to help put an end to apartheid in South Africa. You know this was a moment that made a lot of sense to us. We were trying to get the University of Texas at Austin to divest its investments in South Africa. You know we rallied, we raised money. You know we rode petitions and you know this was a moment when, in this country, black Americans and slavery rallied for the continent.

Speaker 4:You know we marvel at individuals from the continent who are not supportive, black people who live here, who are not supportive of reparations. I mean our thinking. Well, first of all, you know we're talking about individuals, as we said, who were denied those 40 acre land grants at the end of the Civil War and who survived those 100 massacres, 100 plus massacres. When you migrate to a country, you migrate to its history and to its obligations. And I have always wondered like why is it that immigrants, black and white, who have come here for the American Dream, did not roll up their sleeves immediately and say what can we do to help the black people who helped build this country and made it possible for all of us to have a shot at this American Dream? You know, I want to hear from people on the continent who say we're not going to allow the US government to put any more defense bases thank you On the continent until you give black Americans sense of US slavery reparations. We're not going to allow more American corporations to come here and exploit our country until you do that. That's the kind of unity I'm looking for and if you have ideas about how that can happen, we definitely would like to hear them.

Speaker 4:But there was a time when there was more of a sense of yes, we're all in this together.

Speaker 4:Our stories are not the same, our histories are not the same and say you know, there are many, many, many black people in this country who are not descendants from black people who are enslaved in this country do have a reparations claim to make.

Speaker 4:It's just not a claim that should be put at the feet of the US government. If you are a descendant from people who were colonized or enslaved in Haiti, that claim should go to France. Now, france is a curious case because France forced Haiti to pay it reparations, so Haiti needs to get that money back, plus interest and reparations. So if you are descended from someone from Jamaica, from Trinidad, from Artiga, that claim should go to the UK, and in fact there is an organization called CARACOM that is working to obtain reparations for individuals in those Caribbean countries. Interestingly, they do not include black American sins of US slavery in their claim. Nor should they. But the reverse is also true. Black American sins of US slavery should not be compelled to include all the black people from the diaspora in the claim that they are bringing to the federal government.

William Darity:Thank you. I want to make a very brief comment that our goal is to eliminate the racial wealth gap in the United States, which is a task that would require an expenditure of upwards of 16 trillion dollars. That expenditure must be made directly to the eligible recipients, and indirect measures will not ensure that you will eliminate the racial wealth gap. So I'm passionately in favor of measures that would improve the financial position of HBCUs. You know I mentioned my idea about building their endowments. Think that the idea of ensuring that they receive the allocations that have been made to them.

William Darity:You know, the state of Tennessee is another example where what was pledged to these institutions never has actually been delivered. I think that's all true, but I don't think that improving the status of HBCUs will eliminate the racial wealth gap. And here's the critical statistic that I want to introduce in that manner, for many, many years, white heads of household who have never finished high school continue to have a higher level of wealth than black heads of household who have college degrees. So the wealth differential is not something that's driven by educational disparities. It's driven by the disparities in resources that families have the capacity to deliver to subsequent generations. It's the intergenerational transmission effect that is really the key, and we want to interrupt that with a major intervention that would eliminate the difference in wealth between black and white Americans.

A.Kirsten Mullen:Thank you, Dr Darity. We have time for one last question. Oh, at least I see you standing back there too.

Speaker 5:I'll ask them privately, if I can, ok, ok go ahead.

Speaker 13:Thank you, hi. I'm Lloyd Kirkendall. How you doing? I've been reading your books since November and I think it has a lot of great strategies, especially coming from Cali House and Randall Robinson. So I think it's wonderful with the historic part. But my question is what are groups like the ADOS and the INTOBRA saying about your reparations plan?

William Darity:Excuse me. Well, I guess ADOS is somewhat heterogeneous, so I guess it would depend on.

Speaker 4:Explain what you mean by that.

William Darity:Well, I don't know. Ados, my heterogeneous, it's a group called American Descendants of Slavery, and by heterogeneous I think that there are people with different attitudes or opinions within that group, whereas NARC and INTOBRA are formal organizations that have a leadership that expresses their point of view. So I can't say what the range of opinions are in the ADOS group without knowing who the specific individual is you have in mind. But I can say something about NARC and INTOBRA, and their position is the antithesis of ours on almost every point. They don't agree with us about the eligibility standards. I think they want a universal program of reparations for anybody who is black in the United States.

William Darity:We think that other folks who are black in the United States, who are more recent immigrants, certainly have claims for atrocities that they've been subjected to, but it's not the claim that we're making for individuals who are descendants of the families that were denied the 40-acre land grants at the end of the Civil War. They have no criteria or standard about what the amount should be. They're non-committal on that. They are fervent advocates of local and state reparations programs, which we view as a detour, and they also want the monies to be funneled through something that they're calling a national reparations trust authority, and that's the organization that would be responsible for making decisions about how reparations funds are being used. And we think the money should go, as it has to other victimized communities, directly to the eligible recipients so that they will have full discretion over the use of the funds. So complete disagreement with Anarkin and Cobra Also.

Speaker 13:I'm also with Ms Barbara here. What she says is I also think there should be systematic change. Oh, you're very welcome, that's it. That's it, that's it.

A.Kirsten Mullen:Oh, thank you.

Langston Clark:Thank you all for coming. Thank you for joining this edition of Entrepreneurial Appetite. If you like the episode, you can support the show by becoming one of our founding 55 patrons, which gives you access to our live discussions and bonus materials, or you can subscribe to the show. Give us five stars and leave a comment.